Mel relishes running the “Enchanted Jungle,” a roadside attraction in the Everglades filled with live parrots, concrete dinosaurs, and other unexpected wonders.

Short story | 4,400 words

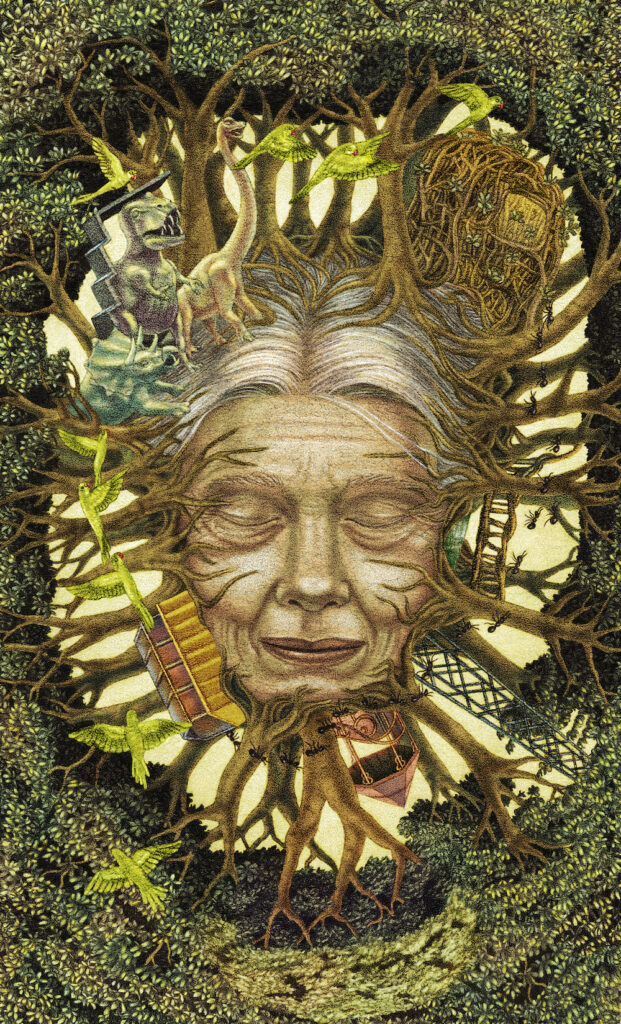

Under the placid gaze of a concrete stegosaurus, I open the gate to the Enchanted Jungle’s parking lot. As a child, opening the gate to the parking lot each morning was my favorite task. Even now, at age seventy-five, I love it.

The stegosaurusis wearing a garland of flowers. During last night’s thunderstorm, winds had torn flowering jasmine vines from a nearby fence and wrapped them around the dinosaur’s neck. It’s a festive look.

Guidebooks call the Enchanted Jungle a “roadside attraction in the Everglades,” but I don’t think that captures the essence of this place. Here’s the best description I have come up with over the years: “It’s a park filled with science exhibits created by people who believe in fairy tales.” My mom and dad believed in science, believed in fairy tales, and believed in happy endings. I suppose you have to believe in happy endings to buy swampland in Florida, build life-sized dinosaurs, and assume people will pay to visit.

A flock of monk parrots circles overhead, chattering as they fly. I stop for a moment, watching the birds. The parrots change direction, but always stay together. Biologists say a flock of birds has no leader. Each bird reacts to the movements of the other birds. Silhouetted against the sky, the flock looks like a single organism—an enormous amoeba, maybe.

I’m surprised to see the parrots flocking in the morning. At this time of day, they’re usually foraging for food in groups of two or three. They form a flock at dusk just before they return to their large communal nest. But today, something’s different.

Maybe last night’s thunderstorm damaged their nest. It had been a doozy of a storm. A crack of thunder, so loud it sounded like an explosion, woke me from a sound sleep. For a time, I lay in bed and listened to the old house rattle and creak around me, hammered by the rain, buffeted by the winds.

When I finally fell back to sleep, I had a strangely intense dream in which the sounds of the storm became the rattling of machinery. I was working with family and friends in an enormous factory. My mom and dad were there. So was my younger sister, Carol. I was overjoyed to be working with them, even though I didn’t know what the factory was making. In the dream, that didn’t matter. What mattered was I was part of something much bigger than myself.

Since my mother’s death, waking up alone in the empty house has felt sad and lonely. But today, I woke up from my dream feeling great, confident that it would be a wonderful day.

I pick up the walking stick I had left leaning against the fence. In the parking lot, I stop by the gazebo that serves as the park’s admission kiosk. Decades ago, Dad built it from reclaimed materials, having made friends with a demolition crew taking down a row of mansions in Miami. His friends on the crew saved him elegant railings, wrought iron gates, gable windows, and more. Dad assembled these unlikely elements to make a gazebo in an architectural style that one travel writer described as “Florida eccentric.”

For the past few years, Mom had spent every day sitting on a patio chair in the gazebo, collecting admission fees and selling “Enchanted Jungle” T-shirts. She greeted each visitor with a smile. A month ago, at the end of the day, I had found her here, slumped in her chair, still smiling. Her body was warm in the Florida heat, but she was no longer breathing; her heart had stopped beating. The paramedics, when they came, said she had died of a stroke. “It was fast,” they said. “She was gone before she knew it.”

The gazebo is empty now except for Mom’s chair and the donation box I put up last week. My hand-painted sign says: “Suggested donation: $5 per visitor.” Nearby, five arrows on a signpost point the way to the park’s five attractions: the Parrot Tree, the Alien Contact Beacon, the World’s Largest Ant Farm, the Dinosaur Trail, and the Mangrove House.

All the arrows point in the same direction. There’s only one path, but Mom thought the signpost looked better with five arrows.

I head down the trail. I’m almost to the Parrot Tree when my cell phone rings.

“Melissa, are you okay?”

Carol is the only person who still calls me Melissa. I’ve been Mel to everyone else for decades. Right after high school, Carol married Tom, her high school boyfriend—a sweet but unimaginative young man. Tom’s father was an elevator mechanic and Tom had become an elevator mechanic, a well-paying job that didn’t require imagination. Tom and Carol moved to Miami, an hour-and-a-half drive and a world away from the Enchanted Jungle. There they had lived a middle-class life in the suburbs—a lovely home, three children, and a well-tended garden that looked like everyone else’s well-tended garden. Now that the children are grown up, Carol and her husband live in a senior apartment complex.

“I’m fine,” I tell Carol. Actually, I’m much better than fine. The good mood that had lingered from my dream is with me still, despite the loneliness of the empty gazebo.

“The weather report said you had a terrible storm last night,” Carol says. “I was worried about you. That old shack could blow to pieces around you, killing you in your bed.”

Our old family home has seen better days. The house was here when Mom and Dad bought the land seventy years ago—a ramshackle bungalow by the side of the road with the Enchanted Jungle in its backyard. The front porch sags a bit more than it used to and some of the windows leak, but the house isn’t about to fall apart around me. My sister’s mind always goes to the worst thing that could happen. I take after Mom and Dad. I believe in happy endings.

“The house didn’t blow to pieces,” I tell Carol. “It’s fine and I’m fine. I’m heading out now to check the rest of the park for damage.”

“The trail will be wet,” Carol says. “Be careful. You could slip and break your leg.”

“I have my walking stick,” I tell her. “I’ll be careful.”

I don’t tell her she had been driving a forklift in my dreams the night before. I don’t tell her we were all singing as we worked. I don’t think she’d understand.

After Dad died of a heart attack three years ago, Carol started saying Mom and I should sell the Enchanted Jungle and move to the senior apartment complex. After repeated refusals, Carol gave up. But now that I’m alone, Carol has started again.

“You just can’t stay there by yourself,” she tells me. “You need to retire. Come and visit us for a while. You’ll see how much fun we have living here.”

Carol doesn’t seem to understand that the Enchanted Jungle is not a job. It’s my home, and I don’t want to leave it. “We can talk later,” I say. “I’ve got to go now.” I say goodbye.

The flock of parrots flies over my head. With a rustle of wings, they settle into the branches of the big gumbo limbo tree that Mom called the Parrot Tree. The parrots’ communal nest—an enormous tangle of sticks and grasses about the size of a refrigerator—is near the top of the tree. There are openings leading into the tangle. Inside are many chambers where parrots can lay eggs and raise their young or huddle together when the weather is cold. The nest looks undamaged.

A parrot perched on one of the lower branches bobs its head, watching me intently. “Hey, dude!” the bird says in a scratchy voice.

“Hey, dude,” I say to the bird. When I was a teenager, I taught one of the parrots to say “Hey, dude!” That parrot taught other parrots.

Parrots in the tree echo the first bird’s call, shrieking, “Hey, dude! Hey, dude!” It’s hard not to imagine emotion in their calls. They sound so enthusiastic. “Hey, dude!” The repeated phrase grows louder as more birds join in.

The first bird laughs, a startling imitation of my mother’s laugh. Mom used to sing to the parrots—then laugh at their attempts to sing along. The parrots learned to laugh with her. Mom used to say she was leaving her laugh with the parrots so she’d never be forgotten—as if that could ever happen. When Carol came to visit last week, we scattered Mom’s ashes by the gumbo limbo tree and the parrots laughed.

Suddenly, the birds take off en masse, with a thunder of wings and a chorus of squawks. Their calls are joyful as they fly toward the Mangrove House, the last stop on the trail. I follow the birds, continuing on the winding trail to the Alien Contact Beacon—an FM transmitter connected to a twenty-five-foot steel radio tower. The tower is still standing, unaffected by the storm.

Dad had worked with a group of ham radio operators to set up the beacon—a narrow band transmission continuously sending the numbers one to ten in Morse code. According to Dad’s calculations, the signal could be detected out past the orbit of Pluto, a little over 3 billion miles away. Dad figured that any intelligent life that detected it would notice a pattern and come to investigate.

A long-time science fiction reader, Dad was intrigued by the possibility of aliens—but he also had practical reasons for building the beacon. “It’ll be good for business,” he told me. “It may never attract an alien, but I know it’ll attract the UFO crowd.”

Dad had a shelf full of books about UFOs, and I had read them all—science fiction novels, books by scientists, first-person accounts by true believers, and scholarly studies that regarded the UFO as a modern myth. I liked the scholarly studies best. Flying saucers, the scholars said, have nothing to do with space travel. They are really about people—our longings and our terrors. We are not alone. Is that a statement of hope—or one of fear? A blessing or a curse?

I continue down the trail. The air is getting cooler, and it feels like a rainstorm is coming. If I keep going, I may get caught in a downpour. But I don’t care. It feels right to keep moving.

Around a bend in the trail, I reach the World’s Largest Ant Farm, a project I started after I graduated from college with a degree in entomology.

In college, I worked with a professor who studied how social insects like ants and termites coordinated their work. A termite mound looks like a random mess of sand, dirt, termite spit, and dung, but it’s a very sophisticated structure, carefully built to maintain a constant internal temperature and humidity despite changes in external conditions. Kick a hole in the mound and thousands of insects will rush to the damaged area. There’s no leader, but the insects will effortlessly work together to do exactly what’s needed to repair the mound.

Individual termites aren’t smart, the professor used to say, but the colony as a whole is brilliant. She called the termites’ collective intelligence “the mind in the mound.” When many insects interact in a complex system, they become something new, something smart, something different.

When I completed my degree, insecticide manufacturers and pest control companies wanted to hire me, but I had no interest in killing social insects. I wanted to understand them. So I went home to the Enchanted Jungle and built a new exhibit: a half-buried shipping container housing a colony of several thousand ants. Dad dubbed it the World’s Largest Ant Farm, but technically, it isn’t an ant farm—those toy ant farms that people buy are sad little death traps with worker ants but no queen. The display in the Enchanted Jungle is a self-sustaining ant colony complete with a queen.

I step inside the shipping container to check for storm damage. The floor is dry; nothing’s broken. Red light shines on large glass panels that offer a view of the secret world inside the ant colony.

Speakers play sounds from inside the colony, amplified for human hearing. The ants are unusually noisy this morning. An ant can produce sounds by snapping her mandibles or rubbing hard parts of her body together. I’ve overheard visitors saying the chorus of clicks and rumbles produced by the colony is creepy, but I like it. The mind in the mound is talking to itself. Thisis the sound of community, like the babble at a cocktail party. The sounds of the ants remind me of the sounds of the factory in my dream.

On the paved patio to one side of the shipping container, I find a line of ants, marching purposefully toward the Dinosaur Trail. Nothing strange about that. A line forms whenever a foraging ant finds a source of food—a dead bug, a granola bar dropped by a tourist, or any other source of sugar or protein. When an ant leaves the nest, she lays down a scent trail that will lead her back home. If she returns with food, she reinforces her trail with a new scent to tell her sisters the way to the food. The other ants follow her trail and lay down trails of their own, guiding all the ants to the food.

As I consider the line of ants, I realize that there actually is something strange here. The ants are all going in one direction—away from the nest. Usually, some ants are going out to get food and others are returning to the nest with food. I’ve never seen anything like this before.

I follow the ants as long as they are on the Dinosaur Trail. When the trail meanders to the right, the ants go straight, heading directly toward the mangroves. I stay on the trail. Maybe later I’ll follow the line of ants and find out what’s going on, but not just now. I won’t feel right until I’ve checked the dinosaurs and the Mangrove House for storm damage.

All is well with Pokey, our concrete ankylosaur. Polacanthus foxii, thesmallest of the ankylosaurids, is just four meters long and a little over a meter high—the perfect size for kids who want to climb on a dinosaur.

Pokey is the first dinosaur Dad built. An aspiring artist with experience in construction, Dad welded steel rebar to create a sturdy frame. He covered the frame in chicken wire, and then layered concrete on top of the chicken wire to make the dinosaur’s unbreakable skin.

After finishing Pokey, Dad recruited a group of art students to make more dinosaurs. At a small university an hour to the north, he gave a guest lecture on the history of dinosaur sculptures, starting with Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, the natural history artist who made prehistoric beasts for the grounds of London’s Crystal Palace in 1853, and ending with Pokey, our ankylosaurus. Dad’s lecture was apparently quite compelling: six students from the class were inspired to create prehistoric beasts for the Enchanted Jungle.

For one glorious summer, the students lived in an old RV and two big tents. Mom fed them on chili and beans, cornbread, spaghetti, pizza, and lasagna—and the students made the Stegosaurus by the gate and the other dinosaurs on the trail: the Triceratops, the Brachiosaurus, and the Tyrannosaurus rex.

When they arrived, the students thought Dad would lead them, but that wasn’t the case. Dad’s attention was always shifting. He showed them the methods he used on Pokey and let them find their own way. Walking among the dinosaurs, I thought about all the people Dad had enlisted to help build the Enchanted Jungle—the ornithologist who studied the monk parrots, the ham radio operators who helped with the Beacon, the architect who built the Mangrove House. It seems to me that these people were like the parrots in flight—leaderless, but always reacting to the actions of those around them. Somehow all their individual reactions add up to a coordinated effort, the creation of the Enchanted Jungle.

The Tyrannosaurus rex has a steel stairway leading to a platform in the dinosaur’s head. Thinking of Carol’s concerns, I carefully test each step as I climb up. From the top, I look out over the mangrove swamp and the bay beyond. In the wind, the mangrove branches are moving, making the forest look like a restless animal crawling out of the sea. Among the waving branches, I see flashes of light—reflections from something silver. The restless energy that has kept me moving intensifies. What could those flashes of silver be? Mylar birthday balloons blown in by last night’s storm? No, something much bigger than that. Something important.

In the western sky, towering thunderheads are growing taller by the minute. I leave the viewing platform and head for the Mangrove House, passing a pack of three Velociraptors. They were Dad’s last effort before the heart attack that killed him. Dad called them Athos, Porthos, and Aramis, but most visitors knew them as Larry, Curly, and Moe. All three are grinning, showing their sharp teeth. Dad loved this trio because these dinosaurs were thought to hunt in packs. Dad had always been a fan of cooperative action.

Around a bend in the trail just past the Velociraptors, I see the flash of silver in the mangroves again. Something big. Something solid. I look up to see a giant silver disk resting atop the mangrove trees. The branches bow beneath its weight—but there are many branches and together they support the craft. I laugh, looking up at the flying saucer. It’s unbelievable—a prop straight out of central casting.

A couple of decades ago, Dad tried to buy a flying saucer that had been part of an advertising display. A souvenir shop in Roswell outbid him, and I think it was just as well. That saucer had been way too shiny and perfect to look like a working machine.

The saucer in the mangroves looks exactly as I always imagined a flying saucer would. About twenty feet in diameter, its silvery surface is streaked with black—burn marks from friction-generated heat as the craft passed through the Earth’s atmosphere. There’s something that looks like a grab bar beside something resembling a hatch. I see a few circular ports surrounded by blackened metal (exhaust ports, maybe?) and other ports (maybe for sensing instruments?). The metal surface is marked with black patterns—letters in an alien alphabet, perhaps.

I imagine the saucer diving out of the sky—attracted by Dad’s beacon, caught in the storm. The clap of thunder that woke me would have covered the sonic boom caused by its descent through the atmosphere. I know it’s impossible, but it’s here and it belongs here in the Enchanted Jungle. The signpost in the parking lot has room for another arrow: Alien Spaceship, this way.

I lift my phone to snap a picture of the Alien Spaceship, but a thunderclap makes me jump. The photo is a blur—a confusion of mangroves and lightning. I text it to Carol anyway, with a message: “The aliens have landed.”

It’s raining now, great big drops that bounce off the path. The mud is slippery and I’m glad I have my walking stick. The trail that winds to the right of the Alien Spaceship leads to the Mangrove House. There, I’ll find shelter from the rain.

Mangrove House was created by Clara, a German student of Baubotanik, or “building botany,” a field of architecture that grows buildings from plants. The summer I turned eighteen, I helped Clara graft fast-growing young mangrove trees, joining their roots and branches to form a room.

While we worked, Clara talked about trees. “People think of each tree in the forest as separate from all the others, but that is not so,” she said. She told me about how aspen trees reproduce by sending out roots that stretch away from the tree. The roots send up shoots and those shoots become new trees. “That’s why all the aspen trees on a hillside change color at the same time,” she told me. “They’re all the same tree. All connected.”

I cross a bridge made of mangrove roots, stepping carefully so I won’t slip, ducking under low-hanging branches. Then I am in the Mangrove House, surrounded by leafy walls, standing on a floor made of matted roots. The light is dim and the air smells of swamp water and rain. I can hear parrots talking softly among themselves in the branches around me—soft chirps and murmurs with an occasional chuckle that echoes my mother’s laugh. The parrots sound calm and content, just as they do when they are settling into their nest for the night.

I make myself comfortable on a chair Clara made from twisted mangrove branches. Over the years, a thick layer of moss had grown on the branches, forming a cushion of sorts. Damp and soft.

Overhead, the thunder rumbles. Lightning flashes, briefly illuminating the leaves above me. The urgency that made me eager to keep going has eased. I think about the aspens on their hillside, the parrots in their nest, the ants in their colony. I think about connections.

An ant scouting for food lays down a scent trail. Another ant finds that trail and follows it. Does she realize that she’s following a chemical trail? Or does she just think: This seems like a good way to go. Does she feel a sense of urgency that pushes her along, that says, Yes, this is your path. Don’t stop now. Keep moving.

Looking down at my foot, I see that moss from the mangrove branches has crept up onto my ankle, caressing the exposed skin between my sock and the cuff of my jeans. It doesn’t surprise or frighten me. It seems right. The moss and the mangrove are connected, and the moss is connecting with me.

My phone rings. It’s Carol. I have to answer or Carol will panic and do something crazy like calling the county sheriff to come check on me. Besides, I want to tell her that she doesn’t have to worry. I am right where I belong.

“What was that weird picture you sent?” she asks.

“An Alien Spaceship landed in the mangroves,” I say.

“What are you talking about? Where are you?”

“In the Mangrove House,” I say.

“What are you doing there?”

“Listening to the rain drumming on the Alien Spaceship.”

“What? Stop joking, Melissa. That’s crazy.”

I wonder if Carol can imagine what it is like to be so close to all your sisters, always comforted by the scent of the nest. Can she understand how I long to be part of a greater whole, one tree in a great grove of aspens, connected to all the others, roots tasting the sweet loamy soil by the bank of a stream and at the same time the soft chalkiness of dissolved calcium near a limestone outcropping?

“I’m feeling connected,” I say.

The moss on my ankle has engulfed my foot and is halfway up my leg. I watch it with interest, thinking about the aliens in the Alien Spaceship. There is no reason to think that these aliens are like people. Suppose they are more like ants or aspens or flocking birds. Suppose they are like the mind in the mound, many individuals contributing to a great effort that no individual can tackle alone.

If the aliens are like that, they might see people as lonely and broken, each one disconnected from all the others. They might want to help us connect. Perhaps, over thousands of years, they have learned to connect with others—with parrots and with ants and with trees. Perhaps they guided me here so that I could join them.

“Melissa,” Carol says. “Mel! What are you talking about?”

“Connection is a good thing,” I say.

The lightning flashes overhead and my phone drops the call. I never do find out what Carol thinks about connection. But that’s all right.

I feel my consciousness spreading out. I listen to the rain and I think about where those raindrops came from. This storm started with water evaporating from the Gulf of Mexico. The warm wet air from the Gulf flowed north until it met a mass of cold air that slid under the warm wet air, pushing it higher and higher. Way up there, where the air is cold, the warm air cooled and the water condensed into rain. That rain is now falling on the Alien Spaceship, trickling through the leaves, and dripping down on me. Eventually, that water will trickle down into the sea. A great circle, and I am part of it.

I could leave this chair made of trees. I could stand up. I’m sure I could. Nothing is stopping me. But I don’t have any urge to leave. I hear a chorus of clicks and squeaks and rumbles like the sounds of the ant colony, like the sounds of the factory in my dream. The aliens want me to feel at home.

I smile, thinking of the ants and the mind in the mound. A memory flickers into my consciousness. One pest control company wanted to develop an ant bait that incorporated the scent that leads ants back home. The ants would follow that scent willingly to their deaths. The ants would think, Yes, this is the right way. We’re going home.

That memory fades. It’s not important. Overhead, a parrot laughs like my mother. Yes, I belong here.

Are these my thoughts, or the thoughts of the aliens? I’m not sure and I don’t think it matters. I can sense the aliens—but they feel like a part of me. They welcome me as if I am a part of them.

If Carol comes to look for me, she will be welcome too. Visitors following the Dinosaur Trail will be welcome. Anyone who comes here looking for a place to belong will be welcome.

I believe in happy endings.

“Not Alone” copyright © 2025 by Pat Murphy

Art copyright © 2025 by Chloe Niclas