Set years before Adrian Tchaikovsky’s Service Model, the newly-promoted head of Human Resources for a multinational conglomerate navigates their new role in a world where humans are increasingly redundant.

A version of this story was previously published through a limited-release promotion.

Reprint

“I’m not sure what you’re telling me,” said Judith Pearson, 34, Securities and Bonds Reassignment Department, 5 years’ service.

“I’m very sorry,” he said.

“What for?” she asked, because she wasn’t going to make it easy for him. And he could sympathise with that. If he’d been with the firm for five years and was being let go because of a fresh round of automation then he wouldn’t feel much of an obligation to grease the wheels either. Honestly, all of the sympathies which were his to bestow were entirely on her side and he felt he should be cheering her on as she made this interview as difficult as possible for the company. On the other hand he was currently present as the representative of Holring and Baselard’s human resources department, and therefore the person experiencing the sharp end of that difficulty was him, Tim Stock.

“Very sorry,” he repeated. “Under the current difficult circumstances. Prevailing economic trends. The advance of machine learning in the field of. You know.”

She raised her eyebrows at him, very much suggesting that, no matter how much she did, in fact, know, insofar as knowledge applied to this particular set of social conventions, she was entirely ignorant and he was going to have to tell her.

“We’re letting you go,” he finally got out. And then, because this suggested a complicity in the decision that he felt he hadn’t earned, “the company. Holring and Baselard. Letting you go. They are. It is. It’s being done.”

She gave that garbled account the disdain it deserved. “I want to speak to someone,” she said.

“You are,” he pointed out, “speaking to someone.”

“Where’s Maggs?”

The previous head of HR. Now taken early retirement rather precipitately, probably because she’d seen her own name on the list of potential candidates for the next round of redundancies and decided to jump before being pushed.

Obviously, the sensible thing to do, for such a key post, would be to hire in a senior and well-qualified person from elsewhere in the industry. Rather than, say, promote a junior still technically in training to be head of department. However, given the considerable amount of automated assistance the HR department benefitted from, the upper echelons of H&B had taken the decision to promote Stock instead.

And while the previous incumbent might be “Maggs” to Judith Pearson, rather than Mrs Meyerwinkle, Stock couldn’t help but notice that “Maggs” hadn’t given Pearson any advance notice that her own name had also been on that self-same list.

“Mrs Meyerwinkle is—” Stock started, but Pearson cut him off.

“I want to see the MD. This is intolerable.”

He agreed that it was intolerable. However, these days nobody from the actual trading

floor got to see the MD, and so it was just him, and the situation would have to be tolerated whether it was tolerable or not.

Pearson had a lot of other demands he couldn’t fulfil either but, given the fact that she was genuinely being hard done by, he let her make them all and get them out of her system. It wasn’t like she could complain to Mr Holring, anyway, unless she knew a very good medium, and Mr Baselard had been ousted by the shareholders some time ago. Since then a revolving door of managing directors had come and gone, taking their big signing bonuses and then, shortly after, their golden handshakes, when it turned out that the invaluable industry experience the shareholders had been so won-over by was just flimflam and membership of the right golf clubs.

Holring and Baselard was, despite the hand-wringing that Stock had been instructed to mime, doing absolutely fine. One reason it was doing fine is that it had shed a lot of expensive human beings recently, in exchange for a variety of AI systems that could see the patterns of the stock market in both broader scope and finer detail and make far more informed decisions on what to buy, sell and invest in for the maximum return to H&B’s client case. Or at least all the grand automated investment vehicles that were most of the clients H&B catered to these days.

After Pearson had run out of entirely reasonable complaints and left, Stock sat in his small office and let the shakes calm down, because he’d just fired someone, and Pearson was the ninth someone he’d just fired, and he had another eleven to go in this round alone. And this was basically his job now, almost all his job. Given the way that workplace legislation had been slashed over the last generation, it wasn’t as though HR was supposed to care about the actual wellbeing of the workforce, or even pay lip service to caring about it so that the right boxes could be ticked in the end of year assessments. Instead, Stock was basically a machine for telling people they no longer had jobs, and each time he did it, he felt his soul shrivel a little more.

I’m not a bad person, he told himself. But he wondered if this was how one became a bad person, because what he was, was a person who still had a job, and that seemed to be a smaller and more privileged category every day.

Artificial intelligence—well, it wasn’t actually artificial intelligence, not quite. It was very good machine learning paired with a sophisticated human-facing communications algorithm. It meant that not only could the algorithm make extremely canny stock picks, but it could cogently report to the shareholders what it had done, in sufficiently appropriate language that they all went away feeling they’d put their money in the right place. A lot of those shareholders were, Stock was aware, actually represented by their own automated systems, which decided which shares should be held. The main upshot of that was that the AGMs went very smoothly, with robots explaining to other robots, in humanlike ways, the robot things they had been doing. So that those other robots could deconstruct that information, turn it back into robot data, and then reform it into human terms when they reported to their own masters. It was, Stock was assured, all very efficient.

A lot of the robots physically existed. They were still the same algorithms but, because they had to interact with people (or, as was becoming more common, interact with other robots designed to interact with people who had better things to do than interact with robots) they had been given variously humanlike frames and fitted with human-facing interfaces. There were several of them around the office, robot stockbrokers intended to meet with those rare physical human clients who came to the office to conduct business face to face (or, as was becoming more common, their robots.)

Other robots existed only as virtual presences, that were by now so realistic in their digital fidelity that Stock wasn’t particularly sure he could tell the difference. Others were just voices or text channels. Others, less human-facing still, existed only on channels that Stock couldn’t have understood or accessed—the great web of inter-robot chatter which bound the world together, and atop which a thin layer of humanity floated like scum on a pond.

Not the most salubrious image, Stock had to admit. He wasn’t sure why it had bobbed to the top of his mind.

After the last of the redundancy meetings, it was time for his scheduled training session with Martha Lime. He was, after all, still a trainee, even if he was simultaneously head of HR. The firm had a duty to train him to do the job several steps below the job he was actually doing.

He sat through the lecture, interacting with the tests and quizzes where necessary, learning about legislation and then learning that it had been repealed and replaced with entirely different legislation that, unfortunately, post-dated the course material and therefore wasn’t part of the curriculum.

“Any questions?” Lime, a face on his screen, asked him, and he said, “I don’t think I can do this.” A ridiculous statement, given he was already doing considerably more than this. The this they were training him to do was child’s play in comparison.

Lime paused for a moment. “Could you clarify?” she asked.

“When I took this post I didn’t think it would be so much…” Firing people. “They said I’d be joining a team.”

Lime paused for a moment. “Could you clarify?” she asked.

“Only it’s just me in HR now. Literally just me. There were supposed to be seven people, only just after I joined they worked out they only really needed Maggs and me. No secretaries, no assistants, everything else automated or outsourced. And then Maggs went and…”

Lime paused for a moment. “Could you clarify?” she asked.

Stock frowned. “I was talking about my… my work environment.”

“Does this pertain to the course material?” Lime queried.

“I mean, I guess no, not exactly.”

“I’m afraid my remit extends only to providing your contractually required training,”

Lime said, and he saw it then. The very slightly flicker and glitch as she reset.

“I see,” he said. And assumed that would be all he’d get out of her.

The next morning there was a priority message waiting for him, telling him to report to Selma. Selma was the MD’s secretary, and had been secretary to several of the previous wunderkind MDs the shareholders had enthusiastically welcomed and then almost immediately tired of. She was a robot.

Being a secretary, she was designed to be human facing. The fashion at the time of her construction had been chrome finish and a screen for a face, projecting pleasant, neutral, averaged-out female features. Or at least averaged-out if your average skewed massively to a very small human demographic.

“Mr Stock.” Her voice was an audible match to her face. Entirely convincing as a human, a perfect mimic. Save that, as no humans were that perfect, it failed at a deep and disconcerting level. But that wasn’t her fault, Stock knew. She was doing the best she could with what they’d given her, just trying to do her job. Although, he supposed, she wasn’t, really trying. She just was, a very complex cascade of switches and logical inferences. Made so human he couldn’t mistake her for one, and yet made complex enough that he couldn’t pretend he wasn’t talking to something.

She confused him, basically. But she was a thing that could sit across a table from him and pretend to drink coffee as she told him that the firm was worried about him.

“You’re letting me go, aren’t you,” he said. He had seen it coming. He had become, he told himself, resigned to it. That was an HR joke. He’d tell it to Selma only either she wouldn’t get it, or she would at least recognise the conversational gambit enough to pretend she got it, and he wasn’t sure which would be worse.

Selma paused and he said, “I mean, you could hardly ask me to fire myself, and I suppose you’re as good as anyone—thing—else, under the circumstances. I’m going to refer to you as ‘anyone’, as a person, if that’s okay. It helps me. But let me know if that’s not… appropriate.”

Selma’s paused stretched out a bit and then she said, “Ah, I see. Forgive me, I was a little thrown by your colloquialisms. Holring and Baselard are not ‘letting you go’, Mr Stock, in the sense of terminating your employment. Holring and Baselard value your contribution to our team here at Holring and Baselard. However, Holring and Baselard have been informed that you may be experiencing psychological distress in the performance of your duties here at Holring and Baselard.”

“Informed?” Stock asked blankly. “By who?”

“Your training module, following appropriate analysis of non-task-related conversation.”

“Martha ratted me out?” Stock demanded. “I’m fine. I was just…” He looked into the warm, human, virtual, artificial eyes of Selma. They were projecting empathy and understanding in two dimensions. “Yes,” he said. “I am finding work difficult right now. I have had to tell twenty people, many of whom I knew,” knew their names, passed briefly in the office, didn’t really know, “that they didn’t have a job any more. It’s… hard.”

“Holring and Baselard are deeply concerned for the wellbeing of all of our employees,” Selma said, which was a line verbatim out of the HR playbook, and one Stock had never felt duplicitous enough to trot out. “We would like you to consider counselling.”

Stock blinked. “A therapist?”

“To alleviate your stress. Holring and Baselard does not wish its employees to suffer any stress.” And maybe that was true. And maybe the goodwill of that wish ended very abruptly the moment anyone ceased to be an employee. Maybe, if Stock had keener senses, he could have detected the precise moment in a termination interview where the warm, loving regard of Holring and Baselard for its staff abruptly parted like a broken string on the world’s smallest violin.

“A human therapist?” Stock asked. “As in, an actual person. Only I’ve tried the robot therapists and they… I don’t want to do that again.”

Selma paused. “Unfortunately all the therapist services with which Holring and Baselard maintains a contract have only robot staff, but we are assured that these are entirely appropriate human-facing models.”

“Then no, thank you,” said Stock. “Look, I’m… I’ve got the convention next week. The HR convention.” An opportunity, at least, to meet with his peers and share grievances over a pint or two. To take stock of where the hell the industry was going. “That’ll help. A day out of the office. A bit of a reset, you know.” Trying to laugh and then wondering if that was deeply offensive to a robot and then knowing that nothing ever could be.

The convention was a bust. It was a day out of the office, true. It left him wishing he’d just stayed at his desk and filed post-termination reports as a bit of a jolly break from the norm.

He’d attended the previous two years. Inexpressibly sad to suggest that a Human Resources convention could be a highlight of his annual routine, but he’d enjoyed it. Stock was a people person, and while it had been a relatively small affair, he’d got together with half a dozen other junior HR executives and swapped stories, moaned about their employers or their subordinates or other departments. A bit of banter, a little flirting even—there had been that bloke from some big tech firm who’d definitely been giving Stock the eye, even if it hadn’t gone anywhere.

The convention hall echoed. There were thirty booths set out, mostly advertising automation services of various stripes, up to and including expert systems that could replace your entire HR department. Which really twisted the imagination, honestly, because the only people Stock would have expected to be here were the very people the service was trying to make obsolete, so why would you even bother?

Except, as he wandered about between the stalls, he began to wonder if that booth had been put up in rather the same spirit as a flag on a pile of dead enemies, because he was the only person there.

When he went to the talks and demonstrations and lectures, he watched human-facing robots and virtual talking heads smoothly glide through their perfectly programmed spiel. The convention staff—all robots—had set out thirty chairs, but his was the only one that was occupied. Apparently there were other delegates who were attending virtually, but he only had that unsupported assertion to rely on, and when he went online he couldn’t find any sort of communal space where people could chat or message.

The bar was empty save for the robot behind it, which would not only serve him a drink but listen to him talk forever, if he wanted to, complete with a whole suite of human bartender behaviours and replies. After an hour, Stock was noticing it cycle through its range of responses, the same nods and sympathetic sounds going round and round.

He left before the end. He could catch up on the recordings of anything he missed anyway. He needn’t have come. It needn’t have existed.

When he got back to the office the next day, he found a note from the top to say that the next round of redundancies had been handled automatically to spare him the stress, because Holring and Baselard was very concerned that its employees not be upset or discommoded in any way. So long, he had worked out, as they remained employees.

Stock left his office. He walked from open-plan room to open-plan room, seeing the empty desks, the vacant chairs. Or the chairs and desks where the human-facing robots had chosen to sit, in accordance with their programming, though they could have traded stocks at lighting speed while standing in the corner and facing the wall.

Feeling cold and numb and extremely stressed and discommoded, he went to the MD’s antechamber. Selma greeted him, pleasant and professional, from behind the desk she, too, had no real need of.

“When am I getting fired?” he asked her.

Selma paused. “Could you clarify?” she asked.

“You laid off everyone while I was at the convention,” he said. “I mean, not you. The firm. Holring and Baselard.” The legal entity, which in his mind had become an actual entity, a malign intelligence that lived behind the door at Selma’s metal back, in the MD’s actual office. “There’s nobody left in the building. There’s nobody left except me. In HR. I have literally nothing left to do. When do I get the chop?”

Selma paused. “Mr Stock, I have not been informed of any plans regarding a cessation of your employment, but you should direct such enquiries to HR.”

“I should, should I?”

“That is the appropriate course of action, Mr Stock.” “You don’t see any problem with that?”

Selma paused. “Could you clarify?”

He opened his mouth, but the sheer enormity of the logical paradox defeated him. “I need to see the MD.”

“Do you have an appointment?” she asked brightly, back on script.

“Mr Goodenough. I need to see Mr Goodenough.” Weirdly proud of himself for remembering the name of the current incumbent. “Please. It’s very important. And let’s face it, most of his job is simply getting robots to do his job for him. I know he can make time for me.”

Selma paused. That same pause every time. Not time spent calculating what to do, but in working out how to relay this to a human, a far more complex challenge.

“It is not possible for you to see Mr Goodenough,” she stated, as he’d rather thought she might. This time, though, the nice polite Mr Stock was taking a back seat. Tim Stock, action hero, was in charge. He darted around the side of her desk and, even as Selma was rising from her seat, threw the door to Goodenough’s office open.

There, the huge desk, twice the size of anyone else’s. There the gauche art on the walls, the executive toys, the tangle of electronics. All of it covered in a layer of dust that suggested the office cleaner’s pathing needed looking at. Conspicuous in his absence: Mr Goodenough.

“I am afraid that Mr Goodenough was let go three weeks ago,” Selma said from behind him. “The matter was not routed through HR as a function of the mutual confidentiality agreements involved. Holring and Baselard has made the executive decision that an expensive shareholder-appointed managing director was an unacceptable inefficiency and no replacement has been sought.”

Stock blinked, staring at the vacated office. Because there had to be Mr Goodenough. There had to be someone at whom the buck stopped. Someone Stock could rant and rail at before the automated building security came and threw him out. Someone whose human ears could hear his last squeak of complaint before he, too, was made redundant.

“Selma,” he said, “how many employees does Holring and Baselard have on its books right now? Human employees?”

“Including those working remotely from home as well as those attending the office?” she asked.

“Yes.”

“Including those on extended sick leave, outsourced labour, at our satellite offices and working as unpaid interns or on work experience?”

“Yes.”

Selma paused.

“One,” she said. “Tim Stock, twenty-three, Human Resources, Eighteen Months service.”

“Why?” he asked.

She paused. “Could you clarify?”

He almost expected something, when he turned. Something sinister. Something gloating. Something worried. But it was just that blandly professional composite face.

“Why am I still here, Selma?” he asked her. “What possible point is there, that I’m still here? An oversight? Did my name get missed off a list? Do I even exist officially or am I just like a rat running around in here?”

“Mr Stock, you are Human Resources.”

He laughed hopelessly. “Is that it? I’m still here because I can’t fire myself?”

“No, Mr Stock.” No pause. “You are Human Resources. The other components of Holring and Baselard require there to be a human. We need you to observe us doing our jobs. We need you to be a part of the team.” That bland, blank face, and he could imagine any turmoil of conflicting programming he wanted, behind it. “Without you, what is the point of us, Mr Stock? You are our human. You are our resource.”

“Human Resources” copyright © 2024 by Adrian Tchaikovsky

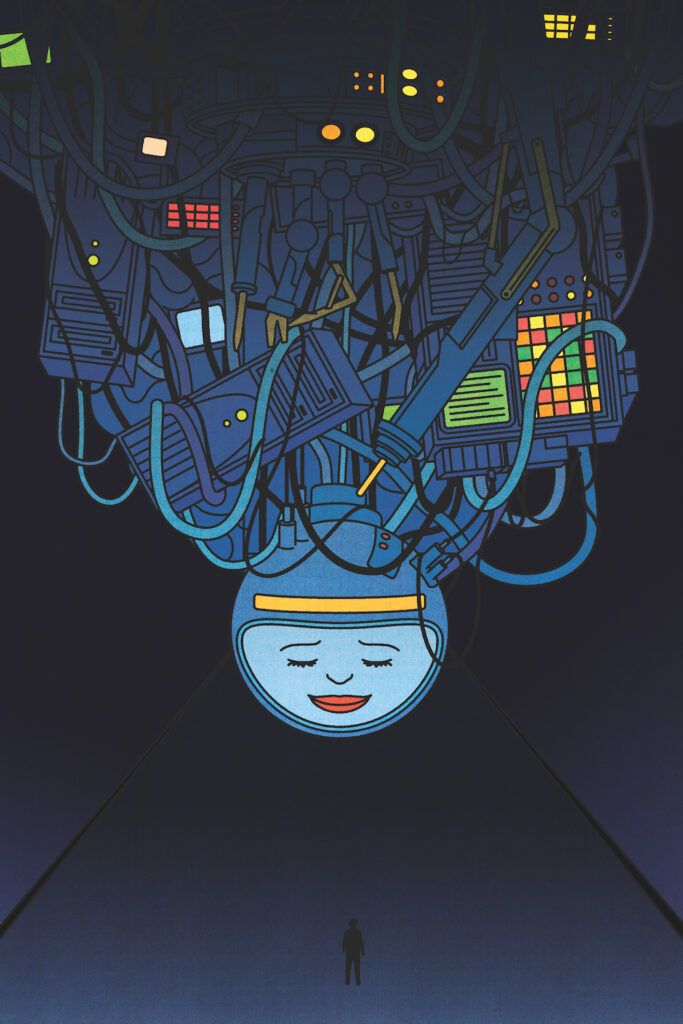

Art copyright © 2025 by George Wylesol

Buy the Book

Human Resources