Those early camp meetings also informed Barnes’s attitude toward racial issues. He’d become addicted, he would say, to the company of Black Philadelphians. He employed them and paid them well. He called spirituals “America’s only great music”; he championed African art. But Gopnik, citing the work of the scholar Alison Boyd, says Barnes’s enthusiasm toward Black culture also tended to be nostalgic and simplistic.

His interest in modernism did not spring fully formed from his rationalist’s head. It took two years of coaching by William Glackens, a high school friend and a founder of the Ashcan School of painters, to open Barnes’s mind to the avant-garde. On an early shopping expedition to Paris on Barnes’s behalf, Glackens shipped back 33 paintings, including Barnes’s first Picasso, his first Cézanne and one of the first van Goghs to reach the United States.

Later, the Paris dealer Paul Guillaume became Barnes’s principal adviser. Without him, “the Barnes Foundation would be a very different place,” according to Gopnik, who detects in Barnes himself a certain “blindness to the cutting edge.” Barnes, a serial exaggerator, later denied the roles played by Glackens and Guillaume. He “even pretended to have discovered modernism before Le Corbusier, one of its founding creators.”

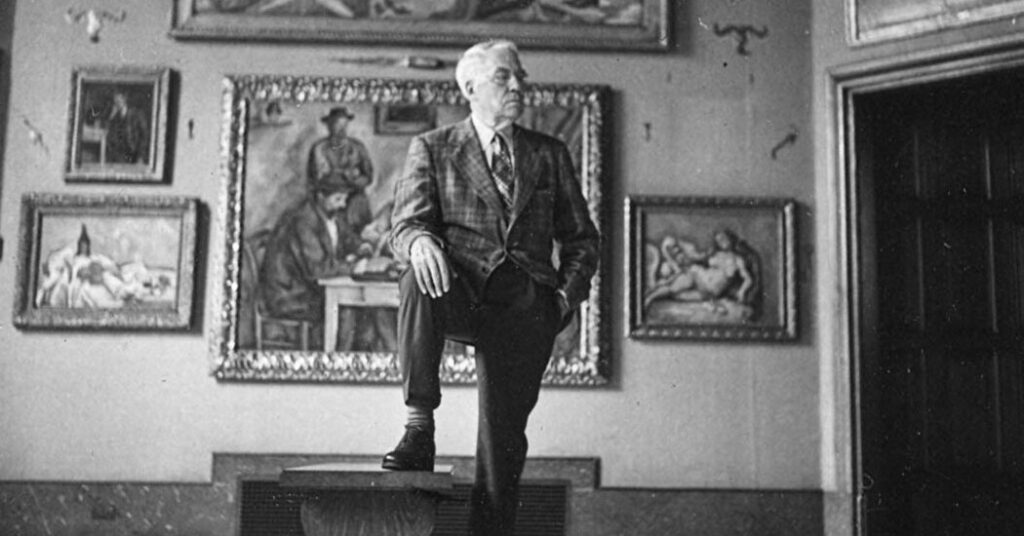

Barnes’s brilliance has occasionally been overshadowed by his interpersonal ineptitude, Gopnik suggests. Similarly, the glories of his collection have eclipsed his thinking and writing as a reformer. Gopnik covers it all, in exquisite balance, concluding that Barnes’s “gifts to posterity, as a collector and thinker, pretty clearly outweigh his own lifetime’s faults.”

In the 13 years since the foundation was relocated to Philadelphia from its original home on a quiet street in suburban Merion — over the ferocious objections of Barnesians who saw the move as a capitulation to Philadelphia’s elites — 2.5 million people have seen Barnes’s beloved collection, its ensembles rehung precisely as he left them. Which is to say, far more people than would have seen the collection in Merion.

Would Barnes still object? Gopnik wonders.

“Knowing Barnes — yes.”

THE MAVERICK’S MUSEUM: Albert Barnes and His American Dream | By Blake Gopnik | Ecco | 416 pp. | $35