We’ve been telling each other stories since our hominid ancestors gathered around campfires in darkened caves. While no one knows for certain, of course, some anthropologists speculate that the drawings on cave walls and rock face carvings all over the ancient world were illustrations of those stories. The date the first written stories appeared is another unknown, but there is evidence for their existence in the Middle East as far back as 4,000 years ago. The modern “short story” as a separate genre didn’t really emerge until the late 18th century, when it seemed to appear all at once in several places. Those works were generally classified as either “realistic” — events that could really happen — or “impressionist” — relying on the subjective consciousness of the narrator.

From there, short-story world gets even more complicated. And so we’ll leave the slicing and dicing of ever smaller subcategories to the experts. For reading purposes, whatever label we use, short stories are brief fictional trips to other worlds. A well-written short story combines an economy of words with tight, flawless plotting. It requires a writer of great skill to pull off a great short story. I say this as a writer who’s never come close to doing it. As a reader, I’m delighted that so many other others have! The five short story collections below are a mix — some are classics many of us read in high school and others are newer works written by contemporary authors. Whether one reads these books from cover to cover or dips in and out as the mood strikes, these collections are gifts to thoughtful readers.

The Very Best of O. Henry: Short Stories by O. Henry

Selected and with an introduction by Bennett Cerf and Van H. Cartmell

Let’s start with the writer whose name graces one of the most prestigious American awards for the genre: O. Henry. We should note even before we start, however, that his name is not in fact O. Henry. He was born William Sidney Porter, and he spent most of his life doing many things other than writing short stories, including being convicted of embezzlement, fleeing the country before being sentenced for the crime, returning to join his dying wife, turning himself in, and serving a prison term. That’s just one chapter in a life full of plot twists. While carrying on with his other escapades, he also wrote newspaper columns and short stories, many of them considered models of the form.

Much of O. Henry’s work is available at no cost from Project Gutenberg, but for those who prefer to read from a book, a good choice is The Very Best of O. Henry (Embassy Books, 2017). With an introduction by Bennett Cerf and H. Van Cartwell, the book collects the O. Henry stories that were considered his best at a time when his work was popular and widely read. It contains his most famous one, which is also my personal favorite, “The Gift of the Magi,” along with its counterpoint, “Mammon and the Archer.”

Compared to some modern short stories, most of these are quite short, often funny or wry, and big on plot twists and surprise endings. Reading them, it’s easy to understand why O. Henry is considered by many to be the father of the American short story. Henry’s advice for writers is timeless: “[The] secret to short story writing: Rule 1: Write stories that please yourself. There is no Rule 2.” O. Henry’s own life could never be condensed into a short story (except maybe by the man himself) and so I wonder, is it a plot twist or a cliché that he died almost penniless and alone, and was not honored by the prize that bears his name until 1937, over 20 years after his death?

Anton Chekhov’s Short Stories by Anton Chekhov

Selected and edited by Ralph E. Matlaw

I am no Chekhov scholar, but one doesn’t need to be to appreciate the Russian author’s short stories. Roughly a contemporary of O. Henry’s, Anton Chekhov, of course, was working on the other side of the world. He wrote fiction to help support his family, starting with humorous pieces he banged out at a rate of up to 100 stories and plays per year. After he returned to school to become a physician, he continued to write fiction but added work on serious themes and produced them at a less frenetic pace. His writing varied widely in tone and style, causing some critics of his time to consider him a lightweight.

Nevertheless, his stories are well worth reading today as much for what they leave unsaid as for what they say. From the story “About Love”: “We talked a long time, and were silent, yet we did not confess our love to each other, but timidly and jealously concealed it. We were afraid of everything that might reveal our secret to ourselves.” My kind of people! That beautiful story is not the only gem in Anton Chekhov’s Short Stories (W. W. Norton and Company, 1979). I can’t get out of my mind his “Gooseberries,” a haunting story about virtue and falsity.

The Short Stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Edited and with a preface by Matthew J. Bruccoli

A few decades later F. Scott Fitzgerald made his debut in the literary world with the publication of his novel This Side of Paradise, which in turn created a market for his short stories in magazines such as Scribner’s and The Saturday Evening Post, prestigious publications that paid authors enough money to make a decent living. Fitzgerald’s turbulent marriage, crash-and-burn lifestyle, and sad end are perhaps better known than the short stories he created from that material, but those short stories are as good as his best novels.

Like the work of O. Henry and Chekhov, they’ve been in print long enough to be available free online, but for readers who prefer a physical book, The Short Stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald, edited by Matthew J. Bruccoli (Scribner, 1998), which includes a bonus forward by the editor, is an excellent choice. For my money, “Bernice Bobs Her Hair” and “Winter Dream” (the precursor to The Great Gatsby) stand out. Both have to do with Fitzgerald’s fascination with class, status and outsiders. The collection includes such Fitzgeraldian lines as: “Dexter borrowed a thousand dollars on his college degree and his confident mouth” and “At eighteen our convictions are hills from which we look; at forty-five they are caves in which we hide.” The stories focus on the characters’ (and the author’s) fatal flaw, one Fitzgerald was ultimately powerless to overcome, despite his constant awareness of the toll it was taking on him.

The Tenth of December by George Saunders

George Saunders claims that his early years working odd jobs (roofer, doorman, slaughterhouse knuckler) and getting a degree in geophysical engineering set him up to become a writer who works with a different set of tools. He is not bragging — his self-deprecating humor and midwestern down-to-earth upbringing instead prevent him from taking himself or his process too seriously. The result is short stories, essays and novels that win prizes — and readers — by the score.

His short story collection The Tenth of December (Random House, 2013) has been widely praised by all the right people and was shortlisted for the Booker Prize. I love it because the stories in it are insightful, empathetic and so darned weird. The title story receives much of the praise, but I quite like “Victory Lap” and “Sticks.” “Victory Lap” takes readers inside the heads of three different characters in a story only 23 pages long. A lesser writer’s attempt to do that might have resulted in a confusing mess, but Saunders makes it seem like the only, obvious choice. My favorite line from “Sticks”: “We left home, married, had children of or own, found the seeds of meanness blooming within us.” From the title story: “What a thing! To go from dying in your underwear to this! Warmth, colors, antlers, an old-time crank phone like you saw in the movies.” Saunders does indeed approach writing with a different set of tools, and for that we, his readers, should count ourselves lucky.

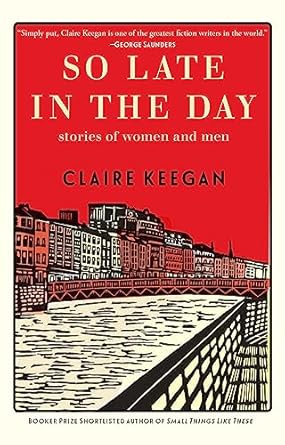

So Late in the Day: Stories of Women and Men by Claire Keegan

Claire Keegan writes short stories and novellas that can stop a reader’s heart. Her latest collection of short pieces, So Late in the Day (Grove, 2023) contains only three stories, each of them precisely crafted and unforgettable. I was shocked to learn that she wrote the title story in front of a class, pretty much off the top of her head, to demonstrate the difference between drama and tension. The story is so full of tension it’s hard to breathe while reading it, and yet there is no drama at all. Nothing much happens during the characters’ shared meals and shopping trips, where Keegan makes clear that their future together hangs in the balance. This sentence summarizes the threat: “That was the problem with women falling out of love; the veil of romance fell away from their eyes, and they looked and could read you.”

“Antarctica,” the final story, ends with a scene that is astonishing and terrifying. I won’t spoil it for anyone who hasn’t read it but will share this moment of foreshadowing from earlier in the story: “I’ve always taken comfort in the fact that hell is populated; all my friends will be there.” Keegan’s works have been adapted for television and film, including the novel Small Things Like These and the novella Foster (as The Quiet Girl). The stories in this collection have also become movies that play in my head, images of people and places I cannot forget, even if sometimes almost wish I could.

Lit Garden is a monthly book recommendation column from Diane Parrish. You can view previous columns here.