A new story set in the world of “The Red Mother.”

Hacksilver riddled with a dragon, saved his family’s farm, and won the secret to raise his dead. Nothing prepared him, though, for the long cold winter when the dead walked…and his family came back!

Novelette | 17,100 words

When the sail lifts, all debts are paid. And so it should have been for me: having done the impossible and restored my brother’s birthright and his life, all my obligations and kin-debt settled for good.

Free as a bird, beholden to none, a man alone on the trail with his horse and his axe. Working on my legend, or perhaps finally working on my retirement.

Raising the dead was why I’d riddled with the dragon, why I’d won her eitr, why I was left responsible for her egg that lay in the badlands above the village. It was, in a fashion, why I’d come here in the first place: to send my brother home to our family farmstead, which I had won back from a thief and murderer.

It had to be his. I certainly didn’t want the place.

Even less did I actually want to talk to him. Or his wife. Especially his wife, for that matter.

Which was why I meant to be long gone before the resurrections really got started. But Ragnar remembered I knew how to dig, and then he needed help with the haying.

To put a crown on it, the snow came early. If you can call it early when it snows every month of the year, up in the bright country. But there’s snow and then there’s snow, and what buried us that day in early autumn was the first salvo of an oncoming cold season with the bit in its grip and no intention of letting up until the sun outran the teeth of the wolf and once again came close enough to Midgard to warm us.

In the meantime, since I was stuck, I might as well be useful. Which is how I wound up helping Ragnar raise his children from their graves.

Ragnar grabbed one side of a rock as big as a shield and waited while I shuffled my protesting body to the other side of the cairn. Canvas rower’s wraps protected my hands from the sharp-edged basalt. Together, we hefted. The stone slid, lifted, ground out of place—and we heaved it to one side and let it arc to the heaps of snow we’d shoveled clear of the barrow.

The gap it left revealed the windings of a shroud. A dry meaty smell arose, like wind-dried fish. The cold breath of the grave was no colder than the wind off the ocean that lay just over the ridgeline. Ragnar grunted and placed one hand on the mummified, cloth-wrapped forehead of his son. He reached into his pocket and pulled out a clay flask, then began worrying at the stopper with his thumbs.

“Wait,” I said. “Would you want to wake up in your grave, suffocating on a winding sheet?”

He sighed. “I thought you were eager to be gone, Hacksilver.”

I used to be proud of that name. I earned it under the first of the sea-jarls I sailed with, and there’s a funny story behind it. Funny peculiar, not funny hah-hah, unless you have a particularly cruel sense of humor.

Anyway, against the odds, I wound up keeping all of my fingers.

It’s a name that carries a wyrd and a doom. That commands a certain—perhaps not respect—but awareness, when spoken. It’s a name that is known.

Sometimes it’s good—or at least useful—to be known. Sometimes it’s better to be an anonymous traveler drifting the landscape.

“Not through a man-height of snow,” I answered.

“We’ll have your brother re-awakened soon,” he said, as if that weren’t exactly the reason I was eager to be gone.

“The latter informs the former,” I replied.

Unfortunately, Ragnar is clever. “You came all this way out of kin-duty; you braved a dragon in her lair; and you still can’t stand the man even though you’d die for him.”

There were so many reasons I wanted to be gone, and only some of them were Arnulfr.

“By the way,” I remarked, “Arnulfr and Bryngertha are buried here, you said. But you never mentioned what became of their daughters.”

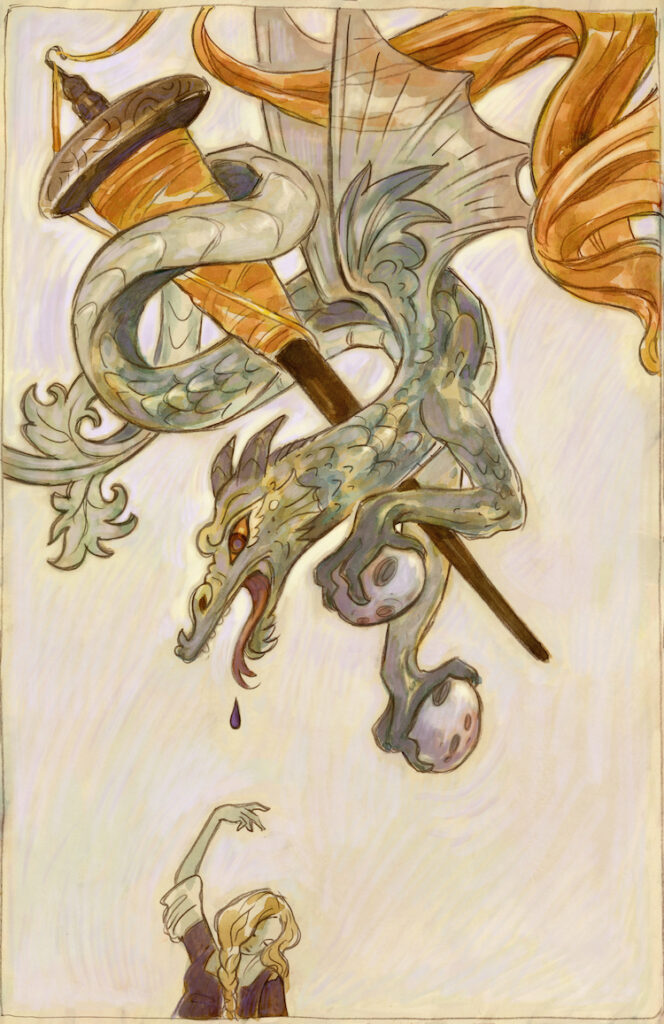

He shrugged. He seemed to be choosing his words with care, which—with Ragnar—is always a sign of trouble brewing. Before he got around to deciding how to manipulate me, though, we were interrupted by a leathery thwack-thwack like a sail swinging to meet the wind. We both looked up, and saw a vast shape unfurl through the veils of ash and poison vapor drifting from the volcano vent on the side away from the ocean. It was the dragon I thought of as the Red Mother.

“Thunder,” Ragnar said. “That is a big one.”

“How many dragons have you seen?” The beast—who had proved less a beast than many men with whom I’d sailed—lofted on crimson wings, membranes shot through with flame patterns that shimmered like gold leaf, each beat swirling the smoke. A fresh pall of ash-blackened snow fell into our hats and our hair.

The dragon rose into the sky, clouds swallowing her lithe shape. I still made out a pair of round objects clutched in her talons, however—two of her three children, taken with her as promised. Which meant that—also as promised—there was still one egg left behind, and it was my job to somehow go get it out of a volcano and find a suitable place to incubate it.

She had said she was going to bring it down to the farmhouse for me. Well, probably easier on the livestock that she had chosen not to.

“I forgot she was your leman.” Ragnar snorted. “But then, who isn’t?”

“Do you want to see if she can hear you from there?”

“Come on.” He tucked the flask of eitr-laced mead back into his pocket. “We’ll have to pull off the rest of the capstones if you want to lift my boy out before we wake him. He’s stiff as old leather.” He paused, as if the horror of what he was saying were a lot, even for Ragnar Half-Hand. “And we still have to get my daughter’s grave opened. And get them both on the sleigh. Aerndis will be waiting.”

I touched the spindle in my pocket for luck. There was a new bat of wool on it, taken from Ragnar’s sheep and of Aerndis’s carding. I wasn’t sure how I felt about the symbolism, but I liked it better than not having a thread to spin fate with.

“Where’s my brother’s barrow?”

Ragnar pointed. “Far side of the graveyard. Shared with Bryngertha, since they died within hours.”

I shuddered.

The crusty old Viking regarded me with a peculiar softness around his eyes. “We’ll come back for them tomorrow,” he said, “snow permitting. It doesn’t seem right to stack them on the sleigh like the carcasses of so many fat seals.”

“We’ll come back for them if the eitr works, you mean,” I qualified.

The corners of his mouth twitched inside his beard. “You’re the witch. You’ll make it work for us, won’t you.”

I pursed my lips. “Was that a threat, Ragnar?”

“Hacksilver,” he scoffed. “When have you ever known me to threaten?”

Ragnar’s children were light as husks when we lifted them, mummified by cold and wind and the dry, dry air under the midnight sun. We loaded them onto the sleigh behind Magni and Ragnar’s flaxen-maned red mare Spóla, who matched my gelding well in size, markings, and color—though she had a more refined head to wear her white star, broken stripe, and snip on.

Then we climbed up on the bench and rode knee to knee along the buried road, in silence. The horses plowed through gray drifts up to their bellies. At least the snow was light and dry and the barely laden sleigh was no impediment. The Red Mother had vanished into the high haze and clouds, which were indistinguishable, and the gray snow and gray sky met one another at the edge of the world without a clear horizon.

We crested a little hill, the horses blowing clouds of steam, and the reek of sulfur cleared from the air a little. The wind picked up, and now I could make out a wedge of gray ocean to go with the gray earth and gray air. You could tell sea from land largely because the undulations on the land were scraped with black where basalt showed through, and the ones on the water were scraped with white and moved rhythmically.

I knocked snow off the wide brim of my hat and stuffed it back on my head in a hurry. The ashy snowflakes that settled on my head stung my skin. I wondered if the dragon had left behind a touch of her eitr.

If I went bald, I’d be spinning sorcery with my ear hairs.

Ow.

The thwack of an axe and the rip of wood splitting, though softened by the snow, echoed as we passed through the village. Figures cloaked and hooded, huddled against the snow, shuffled around the well, turning the winch or hauling heavy buckets with hands red with cold and the burn of whatever traces of volcano and dragon still polluted the snow. The villagers were keeping their mittens dry.

We drew within sight of Ragnar’s house to find a homey stream of common wood smoke rising from the roof-vent, competing with the sulfuric fumes of the volcano. Aerndis stood in the farmyard, her skirts kilted to the knee, chopping kindling with nervous energy.

She looked up when the harness bells reached her, lips thinning as she noticed the sleigh and its bundles. She drove the axe into the block and turned away. When we reached the farmyard, the door was swinging shut behind her.

Ragnar grunted, face pinched behind his muffler. “Put the horses inside,” he said. “Feed them a little. I’ll get the…the kids into the house.”

He set a boot on the block and prized the axe free. “How often have I told that woman, this will rust if she leaves it here.”

I knew his mood. There was no point in arguing it because a fight was what he was looking for. We’d had some good old brawls back in our days of adventure, but my bones ached now and yelling made my ears ring.

I stabled the horses and gave them a sparing ration of hay from Ragnar’s too-small stores of the stuff. The basalt-colored horse I’d named Ormr came to his stall door and hung his head over, nickering, so I gave him a scratch. Apparently he’d forgiven me for nearly getting him eaten by a dragon.

“Sorry, buddy,” I told him. “The fodder’s rationed. You’ve had dinner.”

Maybe by spring his leg would be sound again, and I could take him as a pack horse. If Ragnar didn’t decide to eat him. Between the dragon and the early winter, we hadn’t brought in much hay.

But then I thought, Hmm, and stuffed a little of what there was crinkling into my pocket. To contemplate later.

Inside, Aerndis tended a stewpot that filled the house with rich smells. By the fireside, where the indirect light filtering through the vents under the eaves was brightest, Ragnar cut the cord on a winding cloth, adding another aroma I liked less than lamb and onions. It wasn’t too bad—the bodies were leathery and dehydrated.

“Can’t you do that in the shed?” Aerndis asked as I paused inside the door to pull my boots off. Her voice held more misery than asperity. When I crossed to the fire I laid a hand against her shoulder. She leaned into it and sighed, and we pulled away at the same instant.

“Would you want to wake from the dead in a close, woman?” Ragnar took a small stone lamp from a shelf on the wall, picked the wick out of its shallow bowl, and poured in a spoonful of eitr from the flask in his pocket. The stuff bubbled and hissed against the stone, but did not—as I half expected—eat right through it. In a moment, the boiling calmed.

“Help me get the winding sheets off them.”

A grim task but quickly accomplished. They had not been sewn into their shrouds, only wrapped, with just a few small grave-goods to hand. I might have expected them to be buried seated upon gilded chairs, surrounded by treasures, but I supposed in a plague and a famine even the children of chieftains must make do with a modest funeral. The girl had her distaff and spindle and the gold brooches for her dress, some rings and arm-rings. The boy had a short sword and an axe, his shield laid across his middle, and heavy arm-rings of gold studded with rubies and the cloudy flat-topped squares of polished diamonds.

They both wore stout shoes, to keep their feet for the road to Helheim—where they would spend all of time until time ran out, not having died in childbirth or in battle. The layered leather of the Helshoe soles was scored and worn, marked with the evidence of their journey.

Ragnar rummaged again in his things and came back with a spun glass rod, a delicate instrument whose original use I could not fathom. He had always been something of a magpie: I wondered if he knew himself what it was for.

He did know what use to make of it now. He touched the ball on the end to the eitr and no smoke rose. “Woman, some mead,” he said. But Aerndis was already at his shoulder, holding out a horn.

A glistening drop, faintly luminescent, clung to the ball when he raised it. It fell into the horn, and the mead began to steam and bubble violently as if he had thrust in a fire-heated poker. A golden glow lit the horn from within as the boiling quieted, swirls of light chasing across the translucence.

“Hold her head,” Ragnar said.

I slid my fingers under the dead girl’s braids and lifted her gently. Her flesh was stiff and hard under the hair, which felt disturbingly like the hair on a living woman. I would not bring these lips to mine to kiss, however.

Ragnar tilted the horn against her teeth, where the lips had dried and drawn back from them. Just a little at first, a trickle of shining mead. I expected it to pool and run out of her mouth, probably burning my hands in the process. But it went in…and then it went somewhere. Maybe it was eating a path through her innards, or something else too horrible to contemplate.

Her lips began to soften, to grow full. A pink flush crept through gray and hardened flesh. A quiet and terrible sound came from her, like breath squeezed from a man being pressed under boards and stones. Like the last violent exhalation of a sentry stabbed from behind.

Ragnar leaned back, the horn in his hand empty. He glared at me. “Aren’t you going to say some words?”

I couldn’t see that it was necessary, but a good bit of sorcery is showmanship. I thought it over for a minute, composed myself, and brought my spindle from my pocket, along with the hay.

Some wool mixed with a few strands of my own hair was already partially spun and wound around the shaft. I wiped a few stems of hay through a luminescent droplet of eitr-infused mead, watching the faint glow run up the stalk, then threaded it into the roving and began to spin.

Hay pulled between my fingers like thread, and as the spindle dropped it lengthened far beyond its quantity. Something so brittle and fragile should never have twisted into a fragrant green rope behind the spindle, but it did—and then when I wound it on the shaft it seemed no thicker than a thread.

Ragnar watched, uneasily fascinated, until he noticed me looking. Then he glanced away and flushed so dark his face looked liver-colored in the firelight.

His daughter was looking more and more ruddy as well—her face filling out slowly from the mouth, cheeks plumping, hard drawn-up skin beneath her chin beginning to soften. I drew a breath full of scents that did not go together—savory stew, the cold grave, and mulled mead, plus the warmth of hay and the thunderstorm tang of the eitr—and I…

I stopped myself before I sang. “Your daughter,” I said.

Ragnar looked at me, at the pile of hay growing around my feet. The stalks had begun to shed away from the spindle shaft with each drop, leaving only the thin thread to wind—but the pile was growing. His lips thinned—he must have realized what I was doing and that it would be useful.

“What about her?”

“Her name,” I said.

“Ranndis Ragnarsdottir,” he said. “You might want to step back from the fire with all that hay piling up around you.”

I nodded, did so, and sang. The tale I chose was that of the All-Father finding his way back from Hel; how he returned to his body where it hung on the world-tree. I sang of what he learned, and what he lost, and how he came back to the middle world of the living despite the knife-edged volcanic glass that cut his shoes and the unquiet dead that barred his path.

An unholy groan came from Ranndis’s throat, like the sounds the dead sometimes make when you lift them. It was unsettling the first few times, but was just air or the gasses of decomposition being forced through her voice box. Ragnar groaned too, a more human sound of grief and longing. Aerndis, silent, stood with her back to us, arms folded and head bowed.

A tremor ran through Ranndis. Her feet kicked; her hand spasmed. The soles of her stout boots grew slashes that cut deep to the heart of the leather and beyond. Blood seeped through some of them: black and then red.

Her head turned. She made a human sound now, a sob of grief or unbearable pain. Sunken eyelids opened and the empty sockets stared at me for long moments before swelling orbs filled them. Her eyes were green, and the hair regaining luster on her head was the ripe color of a chestnut—neither red nor brown but both, somehow, simultaneously.

The hay was nearly to my chest, impeding my spinning. As Ranndis sat up I stepped back again. She grabbed at her feet, pulling one up for inspection. Her grave-weathered overdress split at the seam, revealing a kirtle that had once been faultless and white.

She inspected the sole of her shoe, fingering the gashes through which blood still seeped. Then she fixed Ragnar with her gaze, chin lifted, breathing as if she had run all the way back from Helheim. “Papa, what have you done?”

At the sound of her voice, Aerndis turned. Her spine held its stiffness for a moment, but only a moment. Then she sagged, gasping on tears, and swept with her skirts like a great broom past the fireplace and toward her daughter.

Ragnar’s son was also named Ragnar, and as an Auga Augasson I felt for him. We prepared another horn of life-mead while his sister looked on and drank the rest of hers, huddled under a blanket. She was a lovely young woman half my age. When she pulled off the ruined shoes, her toes and fingertips were blue.

“Helheim is cold,” she said. “When I die again, bury me with a sweater. And some mittens.”

I wondered how her marriage prospects would be, having died and come back again. Perhaps I should offer to teach her a little sorcery. She’d been buried with her distaff—she was doubtless already a skilled spinner and weaver. Witch was a bad career, but for those such as us marked by wyrd it might be better than the options.

The second resurrection went much as the first. Young Ragnar—a strapping lad of about seventeen summers—sat up and asked for water, which his mother brought him. She looked up at me, eyes sparkling, and said “Hacksilver, much as I appreciate what you’re doing for the cattle, do you think you could spin that fodder in the hayloft going forward?”

I can take a hint. I left them to their reunion.

When I came down again, Ragnar Half-Hand was standing in the open doorway, letting the cold in and watching the snow fall. A little drift had built up around his feet and I imagined if I didn’t see his wife anywhere it was because she was off somewhere thinking of reasons not to kill him. Ranndis and Young Ragnar had been put to sleep in box-beds along the wall, so the draft wouldn’t bother them—but it was making the fire gutter out coils of soot that probably weren’t doing the stew any favors.

“There’s hay for a month or so,” I said.

He glanced sidelong at me. “You’d make a useful farmer.”

“Sorry,” I said. “I’d rather chew my hand off.”

He made a rude gesture with his maimed one. “No you wouldn’t.”

“Entirely fair,” I answered agreeably, which just seemed to make him grumpier. “Are you going to close the door while you still can? That storm isn’t moving on just because you glare at it.”

He snorted, but shut the door. “I want to go and get your brother and your sister-in-law.”

“Not tonight,” I said. “Or we’ll have four dead to bring back, and I’m not sure we have that much eitr.”

“As soon as the storm breaks.”

“I want to go and get the dragon’s egg before the snow is too deep for the horses. Anyway, if we bring Bryngertha and Arnulfr back now we’ll just have to feed them until spring, and supplies are lean.”

“Mmm. Can’t you spin grain and saltfish the way you spun hay?”

Dammit. Probably, though I’ve never tried. And the hay-spinning had left me not enervated and exhausted, but full of energy and verve. Despite all the day’s labor, I could tell I was going to have trouble sleeping.

And probably regret my insomnia in the morning.

“You want to avoid seeing your brother.”

Also, dammit. “Would you want to be snowed in with any of your brothers for a whole Bright Country winter?”

Ragnar snorted. “I’d rather get down to business.”

Spoken like a true Viking: raid or trade and get home in time for the harvest.

“The dragon egg is business,” I said. “I gave my word.”

He rolled his eyes, throwing his whole head back, and I knew from long experience that I might have won the argument but I was going to regret winning it.

I did sleep, finally, in the long middle hours of the night—and was awakened before dawnlight crept through the vents by the sound of pigs squealing in the byre at the back of the longhouse. Not my problem, I thought at first, and tried to roll over. But the squealing continued.

Irritated, I thrust back the furs and woven blankets in my box-bed. I shoved the door open, letting in a rush of cold air that shocked me fully awake. I thrust my socked feet into my boots and stumped out into the dim hall in my shirt and linens, needing a piss.

The banked fire cast a dim red glow but barely any light—but the hay I had spun and the horns and lamp that had held the eitr shimmered with light like sunrise through a mist, somehow cool and warm at the same time.

Ragnar and Aerndis were already out of their bed, and as the squealing continued and I picked up a lamp full of congealed grease the lad and lass tumbled out as well, fluid with the well-oiled joints of youth.

Maybe I should try a little resurrection. To lubricate the joints that complained as I crouched to blow the fire up enough to light the lamp.

The five of us rushed toward the animals, Aerndis with a torch in one hand and myself holding aloft the lamp, shielding the flame with my other hand so it did not flicker overmuch. By the time we got close, the light of the magicked-up hay made seeing easier.

A sow lay on her side in her pen, crowded in, with sixteen piglets pushing and shoving along her belly. Behind her, in the sheepfold, the ewes were easy to pick out from the ram as they all looked swollen enough to burst.

“It’s not the season!” Ranndis burst out, her eyes wide.

Ragnar glared at me. I shrugged. “I wasn’t expecting that,” I said. “But I don’t know much about eitr.”

“Maybe I should try eating some of that hay,” Aerndis said wickedly.

Ragnar turned his glare on her and she laughed, a rusty sound that grew in ease as she practiced it. She wiped tears from her cheeks, grinning. Then, ever practical, she flipped her night braid over her shoulder and said, “Let’s get a pig rail into that pen before the sow rolls over on her piglets.”

In the morning we hooked Magni and Spóla once more to the sleigh and prepared to climb the mountain. Aerndis brought us heated mead—the regular kind, not glowing—and bread with salty butter. When Ragnar wasn’t looking, she leaned in and said to me, “I’m glad you’re here, you old bastard. With a house full of baby animals, we’re going to need all the hands we can get this winter.”

I touched the axe at my side surreptitiously. Thirty years a Viking to wind up slopping piglets. The gods were laughing.

As we set out, Ragnar and Young Ragnar and I trudging beside the sleigh, it occurred to me that our horses’ names might be a good augury. Magni, son of Þorr, the mighty one. And Spóla, the spool or the wheel—an auspicious name when associated with sorcery.

I wondered if Ranndis the weaver had named her.

I was idling. I focused my attention on snow, stone, and sleigh runners. Young Ragnar had a good hand with the horses and kept them moving forward, not quite to the brink of the crevasse where I had met the dragon but closer than I would have expected them to go. I had been turning over in my mind how we were ever going to get the egg up the cliff from a hole full of poison fumes and charring heat, but apparently the Red Mother had anticipated human fragility: it balanced like a great boulder a furlong below the lip of the crater, on a flattish patch of ground scorched free of snow.

A few flakes drifting down settled on the mottled, flickering shell and vanished with a hiss. I hoped that meant it was still warm enough.

The wyrm said it only needed to be buried by a hot spring, just as one would bake bread in a kettle, so…probably.

“How are we going to handle that thing?” Young Ragnar asked.

Half-Hand looked at me.

Which was fair, I supposed.

I pulled my spindle from my pocket. I could probably do it with witchcraft, though it would leave me not fit for much besides staggering back down the mountain with the horses, and I’d lay even odds I’d have to be dragged.

Well, I’d lay better than even odds that Ragnar would enjoy dragging me, so it was fine if that happened.

But as I gave the spindle a flick and dropped it, and felt the sorcery take hold, I felt not a drain on my energies but a flush of well-being. The desire to dance a step, though I wasn’t sure I could dance while spinning—or spin while dancing. There might be some magic in it if I could, however.

The wool, some strands of my hair wound through it, spun out gray as the ash of the volcano, the bone and ebony spindle smooth and quick. The Ragnars looked away, embarrassed as if they had caught me masturbating. I spun on.

The thread, like the hay, spun faster than expected. I wondered if the eitr permeating the environment was having an effect on my seiðr. Anyway, it wasn’t long before I had spun out, wound, and then chain-plied the whole length of wool.

I eyed the egg. It was bigger than anything I had moved this way before, but it might do.

“Turn the sleigh,” I said. “Back facing upslope, and let’s build a little ramp of stones so the egg can slide or roll up it and there’s no lip to heave it over.”

I burned my hands twice getting the egg harnessed, and Young Ragnar had the bright idea of laying a bed of stones on the sleigh so the boards wouldn’t char from contact, but we managed it. Somebody had to stay with the horses the whole time, because while a dragon egg wasn’t a dragon, it was definitely in the category of Things That Eat Horses. At least as far as the horses were concerned.

Of course, so are mud puddles, especially dark shadows, and unfamiliar foodstuffs.

I used my sorcerous bonds to fix the egg to the sleigh—I could envision too many disastrous scenarios otherwise—and we set off down the mountain. The horses were eager to return home and eager to elude the monster traveling at their heels, so they set off at a brisk walk and Young Ragnar, walking between them, had his hands full keeping them from breaking into tölt or trot. Half-Hand and I jogged beside, keeping an eye on the egg.

It was all going rather well, I thought, when I heard the first cracking.

“Stop the horses.”

Young Ragnar was already doing so, though it was becoming increasingly difficult. The horses in question liked noises coming from the Horse-Eating Ovoid even less than they liked the Horse-Eating Ovoid on its own.

Worriedly, I examined the surface, feeling my eyebrows scorch when I leaned close.

“Fuck.”

A hairline crack, pulsing brighter orange than the surrounding swirls and mottles, ran across the surface on the bottom.

“We’ll seal it with some lead,” Ragnar said. “Let’s keep going.”

I didn’t see another choice. I nodded and, much to the relief of the horses, we started down the mountain again.

The slope grew steeper, the horses setting back on their haunches to navigate the incline, and Ragnar and I followed behind the sleigh managing its descent with the brake and with simple hauling backward. Cold burned through my boots as they grew wet, and the heat of the egg burned my cheeks and forehead.

“How much farther to the hot spring?” I asked.

Old Ragnar pointed. The pale streamer of steam was hard to see against the snow and the pall of ash, but I could make out its shape if I squinted.

The dragon told me I wasn’t bound here as long as I checked the egg regularly…but I am not sure I would trust Ragnar Half-Hand with a baby. Or my brother Arnulfr, for that matter.

I attributed the fact that each of them had managed to bring two children to adulthood more to Bryngertha and Aerndis than to any nurturing qualities in Arnulfr or Old Ragnar.

I’d trust Bryngertha and Aerndis with a dragon. But if we successfully managed to bring her and Arnulfr back to life, Bryngertha would be going back home to the land I’d reclaimed for her and her husband.

I could hear the Red Mother in my thoughts. Take care of my child, snack. I’ll be checking on you.

If anybody bothered to write my song, would its last line be, His fame ended on the sense of humor of a dragon?

We made our way to the spring. Ragnar or Aerndis or someone in the village had built a spacious bathing tub out of smoothed stones. I looked at it longingly. Well, there would be time for a soak once the egg was earthed.

Young Ragnar unharnessed Spóla, limping a little on his cut feet, then swung up onto her bareback with the lithe effortlessness of youth.

“I’ll be back with the lead,” he said, and horse and man took off across the snowy hillside toward the farmstead.

Old Ragnar and I pulled shovels off the sleigh and got stuck into digging. Three strokes of the spade in, he snorted. “Kid knows how to avoid hard labor.”

I laughed, and thought of Ranndis’s haunted eyes. “Coming back from the dead certainly hasn’t seemed to harm him.”

Crunch went the shovel, a steady rhythm like a drum. “He lacks his sister’s imagination.”

There wasn’t much I could say to that. Ragnar could still read my mind, apparently. Or perhaps the trend of my thoughts was obvious. “You didn’t tell me what happened to my nieces.”

“I offered them marriage to two of my bondi who had lost wives to the sickness,” he said. “They chose to travel on rather than come down in the world from landowner’s daughters to tenant farmer’s wives.”

I barely knew Signe and Embla, and I didn’t blame them one bit.

The work was hot and nasty. My chilled toes felt brief reprieve as the heat of the ground worked through my boots, but then they were roasting. Or perhaps steaming is the better word, as steam rose around us. Gritty, steaming mud was what we shoveled from the hole. Water seeped in, not quite boiling.

I was dubious about burying the egg wholesale. Eggs can drown the same as men. But we could prop it on rocks above the water level, and heap earth over it to keep the warmth within.

Young Ragnar returned with the lead and the means of melting it. I soldered the crack in the egg, using an extra layer of lead to be sure. From within, I almost thought I heard a faint rustling sound when I leaned close enough to scorch my ear-hairs.

I decided I was going to worry about that later.

Using the netting and traces I’d spun, the three of us lifted the thing from the sleigh and manhandled it to the nest-burrow we’d dug and lined with stone. We settled it and covered it, then I wrapped it in a veil of protection.

I didn’t want to come back here. But I had given my word to guard the Red Mother’s child. And in return she had given me her eitr.

The spell caught and sank in, silvery radiance vanishing into the mottled ember of the egg and the baking mud that covered it.

We stood for a moment, leaning on our shovels.

“Last one into the bath is a troll’s get,” Young Ragnar said, and began stripping. We rinsed in the cooler runoff from the tub, getting the grit off, and slid gratefully into the hot water.

Steam rose around us, but it was pleasant now. Half-Hand turned, stretching himself against the rim of the tub, and I averted my eyes from the pull of muscle across his back. That was a mistake I had no intention of repeating, no matter how appealing it might temporarily seem.

My body had other ideas, but fortunately the water was cloudy with minerals. It’s not mannerly to corrupt your host—or to accidentally corrupt your host’s son.

We returned to the farmstead in time for a good meal served by the women. Morning dawned noticeably later each day, the Bright Country accelerating toward its winter darkness, so when it did we were already up and fed and dressed by lamplight. I went out to fetch horses for the sleigh, my breath pluming on the air like a dragon’s, and noticed that Ormr’s limp was better. Maybe the cold was agreeing with him.

Spóla and Magni had earned a rest, so I harnessed up a blue dun gelding and a bay mare who looked like they could use the exercise and seemed like they got along. All of the horses—mine and Ragnar’s—were in high spirits, with swishing tails and arched necks.

The sleigh fairly flew across the snow, Ragnar and I perched on the seat at the back, shovels piled in the cargo area at our feet rattling with every drift. We passed north of the village center and reached the cairns in less time than I would have thought possible without clear roads.

Once a man’s exhumed a couple of bodies, one wouldn’t think exhuming a couple more would present any great emotional difficulty. But when the bodies belong to your estranged family, it doesn’t get better.

The flat rocks roofing the cairn were slick with ice. Snow dusted up the cuffs of my gloves, and my boots hadn’t dried completely from the day before—despite spending the night by the fire—and I was soon using a trickle of sorcery to coax them not to freeze solid. I couldn’t warm my feet up, sadly, but at least I could keep the water from turning to a block of ice around my toes. And as long as they hurt, they weren’t frostbitten.

We worked fast and sloppily, the wind biting our ears and noses, burning our fingers through the gloves. The dead were frozen inside their shrouds, stiff with more than mummification. We had to pry them from their icy chambers—gently, methodically, so as not to break them.

I do not care to speak more of it.

By the time we finished, the horses were champing and stamping at the cold. We glided back with both horses pulling with all their strength, Ragnar easing the reins to ask them to spare themselves, them blowing great plumes of breath in the cold and shaking their heads with desire to reach the warmth of the byre. I struggled to steady the cargo and keep my brother and his wife from flying off the sides of the sleigh on the turns.

Before long, we heard the horses we’d left at the freehold calling, and the gelding and the mare called back. Is there a horse there?

There is a horse here!

Fancy that!

They cantered up to the gate and fairly slid to a stop. I cushioned the shrouded bodies, then left them where they were and got off to help Ragnar unhitch the team and bring them inside long enough to dry their sweat before we put them away, so it wouldn’t freeze in their heavy winter coats.

Aerndis and Ranndis met us at the door with hot ale when we came inside, and rarely has anything been so welcome. We quaffed it before we led the horses back to stalls and hay. I would have gone back out for the bodies, but Aerndis shoved Ragnar and me toward the fire and Ranndis and Young Ragnar brought them in. Brother and sister were joking and pushing as they went out the door, but were noticeably quieter when they came back, a shrouded husk slung between them.

I wondered if they were thinking of how recently they, themselves, had been entombed in stone. Shrouded in linen just like the man and woman they now bore in turn.

Aerndis brought us flaky flat bread and a stew of turnips, onions, mushrooms, and the placentas of the sow who’d farrowed. Their strong taste reminded me of liver but the meat was more chewy. I did not overmuch care for it, but I ate all I was given and washed it down with another ale.

One did not complain of another’s food when it was given to you in winter.

The bread was good, chewy and sour with rye, and there was plenty of butter.

When we had finished, Ragnar and I stood and went to unwind the shrouds as before. Ranndis went and fetched the horses to lead them back outside. I thought it was a pretext, but it was her house and if she didn’t want to watch a resurrection, I thought she had the right. Half-Hand huffed after her, but didn’t say anything.

For the best. Maybe he had grown wise enough in the years I had avoided knowing how to find him to realize that he didn’t get to have an opinion, not having been dead.

I did notice that Ranndis was no longer limping, and neither was Young Ragnar. The cuts on their feet had been deep. Either the resurrected healed fast, or those kids were tougher than I had imagined.

The first body we unwound was Bryngertha. I found myself frowning over her dark, matted hair, her dull skin and sunken features. The firelight warmed her gray complexion enough that I could imagine her old, and sleeping—

Why would I want to think such a thing?

She’d chosen Arngeir, and she’d most likely been right in that decision. Sure, it had resulted in her going into exile and dying of the plague, but I suspect I’d rather do that than live with myself if not living with myself were an option I could figure out how to make work.

“Give me the flask,” I said, and we did again what we had done before.

Arnulfr woke screaming. Bryngertha, who had opened her eyes with a wild look and a great gasp, sipped her mead and huddled in blankets and spoke not a word. We wrapped my thrashing brother in blankets and poured the rest of the potion down his throat. When he saw my face, he stopped fighting and let me hold his head up to get the liquor into him.

Something outside, in the distance, howled. Not wolves, but whatever it was carried unearthly, ululating overtones not too dissimilar.

Young Ragnar dropped an empty horn, then cursed all the more manfully and kicked it across the room. I wanted to reassure him that every man here had felt that finger-numbing fear. Aye, and the women too, most likely. But I had been young once, and it wouldn’t calm him to know I’d noticed.

“Voices from Helheim,” said Bryngertha. A little mead slopped over her fingers. Her teeth were still chattering with the cold of the grave, but color grew in her cheeks slowly. “Voices from the grave. What have you done, Auga?”

I didn’t have an answer. I got up to fetch stew from the pot Aerndis had left near the coals to keep warm, and brought it to her. “Eat,” I said.

“Why have you done this?” she asked again.

“I cleared Arnulfr’s name,” I said, going to get another bowl. “You and the girls can go home again.”

“If you’d left us dead the farm would have been yours,” my brother said.

“If I’d left you dead I wouldn’t have wanted it. Here, take this. Eat it.” His hands trembled but the stew was thick and didn’t slop over.

Aerndis buttered bread and passed it around. I knew from her expression that she was wondering how we were going to feed everyone through the winter. I too wondered, but I did my best not to think about it for now. I could spin hay; I didn’t think my sorcery would consider rye berries or dried fish a sufficient analogue to wool or linen. But I would try it, and soon.

As she passed me a mug of ale, she whispered, “Maybe we should have waited to spring to raise the dead,” and I could not keep myself from laughing.

Ragnar Half-Hand shot me a glare. I decided not to twit him about being jealous. He had, after all, his reasons.

Ranndis came back inside, a brief halo of moonlight limning her until she shut the door. What would be a long night had fallen. The cold fell off her in a cataract, rushing across the floor to chill my feet in their thick socks, drying beside the fire.

Bryngertha closed her fingers in the fur that edged her blanket. “Where are my daughters, Hacksilver?”

Having to tell your undead brother’s recently resurrected wife that you don’t know where her children are ranks as one of the worst jobs I’ve ever undertaken, and for me that’s saying a lot. Half-Hand, of course, left me hanging—he got up, stomped into his boots, and went into the darkness muttering about feeding the cows.

All I could tell her was what he had told me: that they had survived, and moved on together. That they had been gone by the time I got here.

Bryngertha did not seem impressed with my excuses.

“You have to find them, Auga,” she said, when she was satisfied that they had been long gone before I ever made it to the scene. My brother watched us through hooded eyes, picking at his stew with surprisingly little appetite for one come back from the home of hunger’s plate and famine’s knife.

I got up to help Aerndis scrape the plates, and as I stood another commotion rose from the byre.

“Oh not again,” said Young Ragnar, heading over.

“What is it?” I asked.

He sighed. “The ewes are lambing. This is starting to seem like a pattern, Hacksilver.”

The unearthly cries outside persisted through the night. I cannot speak for the others, but howls and ululations left me only broken sleep. Would some vast monster break down the barred door to the hall before moonset? Would we have to make a stand before the fire, or scramble into the cold dark to be hunted or to freeze?

I used to be better at sleeping with my boots on. Odd, because I’m more tired all the time now than I was then.

In the middle of the night, one of the cats snuck into my bed, and in the first filtering light of morning I was unsurprised to discover I was sharing space not just with her, but with two tabby kittens and one tortoiseshell. The cat glared at me when I stirred but refrained from hissing. I heeded the flick of her tail and made no moves in her direction as I stood up and took myself and my rumpled clothes into the hall.

Bryngertha and Aerndis, after the manner and obligations of women, must have been up for hours. They greeted me with warm bread rolled up around melted butter, and a bowl of porridge with salt and cream. I sucked it off the horn spoon and drank the ale Ranndis gave me.

Old Ragnar came stumbling out of his bed-close, rubbing his eyes. He took a steaming horn from his daughter and quaffed it. “Fuck me, I should have finished with the animals already.”

“The howling kept you awake also?” I asked.

He glowered at me under hooded eyelids. “Like no animal I’ve heard before.”

A pressure on my neck turned my head. Ranndis had been staring at me with her haunted gaze. She glanced away quickly when my eyes met hers. Bryngertha busied her hands, and Aerndis said, “I think everybody heard it. Young Raggi and Arnulfr are out feeding the horses and cattle; the pigs and sheep are taken care of already.”

“Treasure,” Ragnar called her, and pulled her into his ropy old warrior’s embrace. When I looked away, I noticed Ranndis averting her eyes also. Bryngertha, on the other hand, watched with what seemed to be a little smile of recollection.

My pang of loneliness was foolish. A man’s wyrd weaves as it will and all he can do is meet fate on his feet. Or be swept along, bruised and tumbled, behind it.

I was never meant to have a wife.

Or a husband, for that matter.

Bryngertha stood to bring Ragnar his porridge, and something about her silhouette caught my attention. Suddenly suspicious, I looked Ranndis and Aerndis over with a more critical eye.

Yes, I thought—

Young Ragnar and my brother came in on a blast of light and frigid air. “Damnedest thing,” said Raggi, taking the warmed ale his mother offered.

Arnulfr clapped his hands together, rubbing the cold from his joints. He too accepted a hot drink and curled his fingers around it. “Every one of those mares is in foal,” he said, with a nod to Raggi. “The cows are in calf.”

“They ought to be,” said Ragnar. “If we plan to get any milk from them come spring.”

“Maybe,” said Raggi. “But should they be showing as if it were late winter?”

“I’ve got something else to tell you,” Aerndis began, pushing a hand into the small of her back. All the men except for me turned to her with dawning horror. What she would have said next was interrupted, however, by a pounding on the door.

A loud voice followed, yelling, “Half-Hand! Get out here and explain what black witchcraft you’re wreaking!”

With a sigh, Ragnar finished his ale and went to answer. “Baddur, what over land and sea are you on about?”

Baddur was a big enough man that he had to duck coming under the lintel. He stopped just inside, closing the door on the cold, and said, “There’s sows and nannies and ewes and bitches dropping litters all over the village. The horses and cattle are big as houses, and all of the women are pregnant. Even Old Maude. Even the maids unmarried.”

Ranndis’s hand went to her stomach and I saw that I had been correct.

I was happy enough to let Ragnar deal with the neighbors. That didn’t stop me from eavesdropping.

Baddur took the ale Aerndis brought him. He seemed to glance around finally, his eyes adjusted to the dimness of inside. “Half-Hand, why is your house full of dead people?”

Ragnar shrugged, a gesture twice his size and eloquent of helplessness in the face of events. “They’re not dead anymore.”

Baddur drank his ale, making a face as eloquent as Half-Hand’s shrug and far more efficient. “This is going to mean so many lawsuits, come spring.”

Ragnar said, “I got rid of the dragon, didn’t I?”

I hid a smirk behind my hand. I guess forcing me to go up there and negotiate with her was as good as “getting rid of” the dragon in Ragnar’s mind.

And the air was less acrid, the clouds of ash less pervasive. The snow was clearing, now that the dragon’s influence was gone.

“Anyway,” Baddur said, “the village wants to know, Half-Hand. Why is every woman bearing? Why are sheep lambing out of season and the dead clawing out of their barrows to stalk the night?”

“Oh, is that what we heard?” said Raggi helpfully. “We were wondering.”

The conversation seemed unlikely to wind up anyplace productive. So I was—for once in my life—relieved to feel my brother’s hand on my elbow. He turned me aside and said, in a low voice, “What are you going to do about your nieces?”

I bit my lip to keep hold of my tongue and a gusty sigh. “They’re not your kin too?”

“You won us back the farm,” he said, leaving me surprised by the credit he offered me. “Bryngertha can’t travel to parts unknown in winter with a babe at breast, which—given the evidence—she will have soon. And we can’t stay here: we’re foreigners and freaks, and we’ll be held to account for being alive when the village’s children are dead. Or crawling out of their barrows to terrorize those who loved them in life.”

I pinched my nose against a dawning headache. “Arnulfr—”

“I’m not wrong, Auga. I need to take her home.”

No, he wasn’t wrong. If Bryngertha kept swelling at her current pace she’d have that babe in a day or two. And Aerndis and Ranndis right along with her.

I wasn’t looking forward to the wailing. The noise of all those piglets squealing was bad enough.

“You’re going to travel in winter?”

“It won’t be winter once we get away from Ormsfjolltharp. This place is cursed. It’s still autumn in the rest of the world.”

“Do you think—”

“Can you bring them all back?” he interrupted. Again.

Brothers!

I thought of the few drops of eitr remaining. I thought about what Baddur had said, about draugr creeping from their barrows.

Across the hall, the exchange between Baddur and Ragnar was growing heated. At least they didn’t look as if they were about to come to blows.

That sigh got away from me. “I think I did already. Halfway, anyway. Look, I don’t want to be here either—”

“No,” he said. “But Auga, you’re a warrior. And you have sorcery—”

I glowered at him, but he kept his voice low. “If anybody can find the girls it’s you. You know they’re not safe out there alone without a family name to protect them.”

That was true.

“I have to guard the dragon egg,” I said. “I gave my word.”

“Wait,” he said, and Baddur threw up his hands and turned for the door. “Dragon egg?”

After that, nothing would do except that I take him to see the egg. I warned him that it was just a big lump of mud beside a sulfur spring, and he replied, “Oh good, I need a bath to get this grave dust off.”

I scowled up at him.

I’m somewhat tall but not wide across. Arnulfr is taller and broader, with black hair shot gray and a brindled beard. His eyes twinkle between beard and braids and it’s impossible to stay angry at him.

Even when I would dearly like to.

We saddled up Magni and Spóla and rode out. Spóla was visibly rounder than she had been, but had not yet achieved the spherical proportions of a mare ready to foal.

I could feel the embrace of the protections I’d knitted around the egg. Natural yarn would have charred and crumbled by now, but the sorcery I’d woven into these strands kept it whole.

We were most of the way there when I felt something fiddling with it.

“Ride!” I cried to Arnulfr, and thrust my hands forward.

Magni, always ready for a run, broke into a gallop. The snow was deep and crisp enough that the footing allowed us to sprint, but my heart humped halfway up my neck nonetheless. Still, we arrived at the ridge overlooking the spring without dying.

With relief, I saw that the site looked undisturbed. No people were in evidence, and the mud we’d caked over the egg was a hardened dome, baked like pottery. Flickering light showed in the bottoms of the dried cracks.

I still felt that tug on my spell.

The mud heaved.

“Oh, buggery,” I said. “It’s hatching.”

We went down the hill at a walk, the horses excited and blowing. I swung down when we were close and threw Magni’s reins to my brother. I had to get the wards off, or the baby would die in there, unable to break the shell.

Terror shook my hands. No matter how hardened and jaded a warrior you become, there is always something that can scare you. An angry dragon mother taking her vengeance on me and my kin…that was worth being afraid of.

I chipped the hardened mud away with my axe. The egg heaved and wobbled, making the task more difficult, but the shell was hard as stone and barely showed a mark, even when I slipped and hit it solidly. The warding strands were still there, silvery-gray and wound tight, looking like plain wool in the low sun peeking under the high cloud cover. I tugged them apart with my hands, scorching my fingertips, willing the sorcery to unravel. The thread unplied itself, turning back into fluff, blowing away on the brisk sea wind.

Arnulfr stayed back, holding the horses. “What’s happening?”

“It wants to hatch,” I told him. “Get the horses further back.”

Neither man nor horses needed to be told twice. I found the lead seam and wondered if I should chip that off too. But though I was no farmer, I knew well enough that eggs needed to be left to hatch in their own time, and prying them open risked harm to the chick and was only to be done in emergencies.

Was this yet an emergency? Well, the dragon had suggested that gestation was on the order of decades, and here was the thing birthing prematurely…just like the pigs and horses and cats and women. Under my arm, I sneaked a look at Arnulfr.

Would I have to undo the resurrection to stop this? Could I undo the resurrection? There was no sorcery to undo, though—it was cast, the potion drunk, the bodies and souls reunited.

Shit, Hacksilver, you’ve done it this time.

Something hit the egg from the inside, and a flake of shell as big as a trencher dropped away, nearly breaking my toes. I jumped back, and that convinced me I should peel the lead flashing off.

Fortunately it was soft from the heat, so once I got the pick of my axe under a bit of it and pried it up, it was easy enough to strip away. I wrapped my hands in a fold of my cloak over the mittens and it was almost enough to keep my fingertips from scalding.

Almost enough. But not quite.

I tossed the lead strip into a snowbank uphill from the melted-clean area around the spring. It didn’t hiss, which I thought was disappointing, but it also hadn’t scorched my cloak or mittens black, so there were worse things.

More tapping from inside the egg, and another chunk of shell dropped free. The gap was now perhaps twice the size of my paired hands. Something moved in the window—a shimmer of color and heat, an opalescent translucency. The sharp edge of a beak and the pike-tip of the egg-tooth, tearing a membrane that caught the light.

A twist, a shimmer of scales as iridescent as a fish’s, another resounding tap and a crunch that followed. The horses neighed in alarm—a loud ridiculous screeching-hinge sound for such large animals. Arnulfr backed them away again.

“Auga,” he called, “I don’t think you should be standing there.”

Maybe not. But the green-shot vermillion of an eye filled the gap in the shell and I was transfixed. I could not move or think, only stand in wonder. Was it awe, or did the dragon have me entranced, or was I frozen in fear? I could not tell.

This is what warfetter feels like.

Move! I told myself. My body responded only with dreamlike, excruciating slowness. I stepped back, feeling for the ground behind me. Another chunk of shell broke free.

Now a head emerged, blinking and sinuous, shimmering colors playing over a red-orange hide. The most pointed end of the egg was nearly demolished. The crack the Ragnars and I had mended sagged on scraps of membrane like a leather hinge. One clawed foot grasped the shell-edge and broke it away. Furled wings, damp with stringy moisture, wriggled past the ragged lip.

I stood and watched the baby, bigger than a big wolf—big as a snow cat—come. The shoulders were the broadest bit: once those were out, the rest came loose in an embarrassing face-down slither. The dragonlet emitted an outraged squeak and behind me, both horses reared.

“Auga, let’s go!” my brother yelled.

The little beast struggled to right itself. Its wing was snagged on its talons, and I was struck with fear that it would tear the membrane. Already the bright persimmon color was fading to an intense blue-green at the extremities and along the membranes. I wondered if it was safe to touch.

“Hey, little one,” I said in my most soothing tones. “Hold still for a moment.”

With confidence I did not feel, I reached out and caught the foot that was tangled in the wing. The heat wasn’t intolerable, though I thought it would scald if I held on too long. With a quick gesture I got the claws loose—like unsticking a cat from the bedding, but enormous—and released the dragonlet.

It rolled over lithe as a weasel, and came to its feet. It’s red-gold eyes met mine. Mama? Hungry.

It couldn’t be that hungry: the remains of the yolk sac still clung to its underside, linked to the body with thick veins. I had no idea if it was supposed to look like that on hatching, or if it was a sign of being premature.

Whatever it was it didn’t stop the baby from taking a few steps toward the horses. Hungry.

I interposed myself. We don’t eat horses.

Mama?

I’ve been called many things in my life, but never that one before. “Not the horses,” I said.

“Well,” Arnulfr called. “I don’t know how you think you’re getting that thing home.”

Walking. That was how I planned to get the thing home. Except getting it home, to a farmyard full of prey animals, didn’t seem like the best idea. Just the only one I could think of at the moment.

Arnulfr rode ahead to break trail—on Magni, with Spóla ponied beside. Because Spóla was getting so round he’d had to loosen her girth and the saddle looked like a thread tied around a blown-up bladder. Following behind with the dragon, I could imagine I saw her increasing with every league.

Somewhere, Loðurr was laughing.

About halfway back, my neck hairs began to prickle with the certainty of being followed. I slid my spindle from my pocket and wove some strands of luck and protection. It was easy to throw them even as far as Arnulfr and the horses, which pleased me. Practice pays off, I guess.

The horses snorted and flicked their ears as the cloak of sorcery draped them. Arnulfr looked over his shoulder. “What was that?”

“Magic,” I said.

The dragonlet darted a horned head on a snake-neck around. Its extremities had shifted to a dark green-blue now, the colors chasing the orange-red up and down its limbs with every stride, like the northern lights, or a lapping tide. “Mama?”

“Don’t worry, kiddo,” I said. “We’ll handle everything.”

I hoped I wasn’t lying.

Six dark shapes shuffled above the snowy ridgeline that ran to the right of the road. Bandits, I thought, and spun another loop. My hand stayed low, just in front of my hips, body covering my actions.

Bandits, this close to Ormsfjolltharp. Someone needed to warn the town.

But I could stop them for long enough to manage that. Despite all the sorcery I had been wreaking, I felt ready to take on a polar bear and twenty snow tigers. And I was already spinning. What was spinning a little more?

I took off my mittens and threaded one of my own hairs into the roving, then let the spindle drop, thinking of warfetter. I could touch them with it, leave them blinded, deafened, frozen in place. The power to do so filled me with confidence.

Six at once? That was next to nothing. Why, in the old days—

In the old days, I would have thought hard about laying fetter on three or four. Then, the backlash migraine would have made me useless, and I would have been exhausted for days—

Now, I had more strength than I knew how to use. Huh. But I had been younger and stronger then—

Nonsense, the confidence said. You can manage these with no effort at all.

The baby dragon watched me. Cute strings of juvenile eitr dripped from its mouth every now and then, barely strong enough to leave a smoking hole in the snow. Probably a bad idea to reach out and wipe up the baby’s drool, though.

I wove fetter into my warding as the figures lurched closer, shuffling and dragging through drifts. They didn’t approach like bandits, but like frozen men stumbling out of the wilderness. A ruse, or were they actually travelers in need of rescue?

I’d been cold enough recently enough to feel sympathy.

Well, I could check them once they were incapacitated and see if they seemed like trouble.

They crossed my defile without stopping. I felt a faint tug on the spindle as my weaving parted, and the loop of yarn disintegrated in my fingers. Now I saw them clearly despite snow-glare, and I realized who—or rather what—had risen to face us.

Three dead men and three dead women, their clothes and faces black with basalt earth. Their flesh wizened, wind-dried to the tenure of preserved fish. Their hands clawed and naked in the cold; their eyes sunken away to nothing.

Draugr. Barrow-wights. The restless dead.

“Ride!” I yelled to Arnulfr. “I’ll hold them!”

I had no time to try more witchcraft, and besides my fingers were clumsy. My hands, gloveless, were freezing cold.

I dropped my spindle into the pocket of my coat and unlimbered my axe. The snow was terrible footing over the rocks of the road, but at least it wasn’t ice.

“Stay behind me,” I said to the baby dragon, as the breeze brought us the scent of corruption (faint) and meat jerky (strong).

“Hungry,” the dragonlet argued, and leaped past me to bound up the slope toward the revenants.

“Father almighty,” I muttered. I lurched after it, invoking the names of every Valkyrie I could remember. The axe smote circles as I closed on the draugr. One and then another swiped at me, nails long where the flesh had withered back from them. I ducked and lopped off an arm.

“Sorry,” I muttered. Was there a way to incapacitate them that might leave open the option of resurrection? Now that I had a living, gently smoking producer of eitr right beside me?

The dragonlet pounced, and snapped up the severed arm. In two gulps and a head-bob it was gone. It seemed to like the taste, as it hopped forward and pounced on the next one, snapping the head off and swallowing it like a snake swallowing an egg.

Well, I guessed there was no amount of eitr in the world that could help that one.

If one’s revenant corpse were chomped to death by a dragon, did that have any relevance with regard to what afterlife one found oneself assigned to? Did it count as dying in battle? Would the souls of these people be yanked from Helheim and thrust into the halls of the valiant dead?

Fortunately those were not my questions to answer.

The one-armed wight was still coming at me. I lopped off the other arm, then went to behead it. The thing being tough as boot leather, my axe got stuck. For a horrible moment I kicked at the thing’s chest and levered the axe handle.

With a shredding crack, the head came loose and the thing toppled over. But there were still four more behind it.

With a fine disregard for tactics, the dragonlet crouched atop the wight it had beheaded, gnawing on a desiccated shoulder. “Mama,” it told me. “Hungry!”

I knocked another wight away from it with my axe, but didn’t succeed in beheading. The thing flopped in the snow, but pushed upright immediately and staggered forward. A gash revealed crushed ribs across the torso.

“Fight now!” I told the dragonlet. “Eat later!”

A thunder of hooves surprised me. I glanced over my shoulder to see Arnulfr coming on Magni, spurring him forward despite rolling eyes and ears set flat. I wanted to shout Hey, careful with my horse! But there was no time as my brother charged past me, arcing up the slope and down again. His sword went thunk, thunk! And two more draugr collapsed, their heads rolling downhill.

“Showoff,” I muttered, as the dragonlet heeded me, held one down with a taloned forefoot, and bit the head off another one. I reached over and chopped the head off the one the dragonlet had pinned, because its clacking yellow teeth were gnawing ferociously on the dragonlet’s talons.

At the bottom of the slope, Arnulfr wheeled Magni. A patter of receding hooves alerted me that Spóla was racing back to the barn under her own recognizance, Arnulfr having slipped the bridle so she wouldn’t trip on the reins. He does know his way around animals. Which I suppose makes sense, for a farmer.

Arnulfr charged toward us in a thunder of hooves, only to pull up once he saw we had destroyed the enemy.

“Shit,” I muttered. “You okay, kid?”

“Hungry,” said the dragon.

At least the dragonlet’s gorge of wind-dried villager solved the problem of worrying about Ragnar’s livestock for a few hours. As long as nobody in the village ever found out. Dining on the corpses of a man’s children would, I assumed, be generally considered to revoke any guest-right.

The dragonlet was shivering violently by the time we came in sight of the farmstead. Its whole body had changed to that scale-glittered sea-blue except lingering traces of vermillion on the belly, chest, and the inside of the legs and wings. The wings clamped around its body like a man hugging himself with his cloak.

I had thought of dragons as impervious to the climate no matter how cold or hot, but I guess it was a baby.

Both Ragnars spurred up the hill toward us as we approached. The younger was on Spóla, so she’d made it back safely. The older rode that blue dun.

They slowed as our silhouettes topped the ridgeline. “Halloo,” shouted Half-Hand, waving broadly. “Are you all right?”

Before I could answer, his horse balked, planting all four feet and dropping his head in a transparent threat to buck. Both Ragnars goggled.

The elder said, “Is that a fucking dragon?”

Once assured that it was, indeed, a fucking dragon, Old Ragnar sensibly dismounted his horse and sent his son back down the hill with both mounts—heads up, snorting and stomping—to warn the women. He waited for us, and as we approached the dragonlet asked, “Food?”

“Not food,” I told it. “You just ate six barrow-wights. How can you possibly be hungry?”

“What happened?” Ragnar asked, gesturing to the dragon. “I thought that was supposed to take years to hatch.”

“Hungry,” said the dragon. “Cold.”

“It talks?”

“You can talk to it directly,” I said. “I’m not the dragon translator.”

“Food?” the dragon asked.

“Not food,” I said.

“Definitely not food,” Ragnar agreed. “Hello, dragon. I’m Ragnar.”

“I am hight Eldingorm,” the dragon said.

I hadn’t thought to ask if it had a name. I wondered how it knew its name: had its mother whispered it through the shell? Or were dragons born with their names, unlike humans—

I could drive myself crazy wondering. “I am Auga Hacksilver,” I said, since I hadn’t introduced myself before.

“Mama,” the dragon said.

Ragnar executed a perfect double-take and began to laugh so hard he made himself choke.

“I think it’s cold,” I said to Aerndis, while she stood drying her hands on a rag and frowning down at the dragon.

“Of course it is,” she answered. “You get it over by the hearth and build the fire up. I’ll start heating some rocks for the sauna.”

Ragnar was still snickering, but I ignored him. I had my work cut out convincing the dragon not to go eat the sheep in the byre at the back of the hall. Ranndis brought me warmed ale, and I sat with my boots propped on a hearthstone and thought warm thoughts as my feet began to thaw.

The dragon wanted to climb into the fire when I wouldn’t let it go murder all the livestock, but it listened when I told it to lie down beside the hearth and soak the heat up that way. I didn’t think the fire would harm it, but I did think it would smother the flames in short order, and fill the hall with choking smoke and soot.

Aerndis came back with two buckets of lava stones and tucked them in and around the hottest part of the fire, careful not to smother the coals or knock the flames down. She hung the tongs from a hook on a stand near the long hearth and straightened, hand on her back.

“This is ridiculous,” she said, patting her swelling belly. “I was done with it.”

“Eitr,” I said, helplessly. “You can blame me.”

“Oh,” she said, “I do.” She lowered her voice. “And if anything happens to Ranndis, or to my first grandchild, I will skin you myself. After I plier out your toenails.”

“Understood,” I said.

“Is there anything you can do to keep them safe?”

I was no midwife, but I nodded. “Maybe. Though I’m hesitant to work sorcery when”—I shrugged in the general direction of her belly—“all around you, you see the result. Out of season bearing and revenant barrow-wights. Eitr, it seems, changes everything.”

She pinched her nose. For a moment, I saw her as she had been when we were both young, the familiar gesture like a summoning. “Well, let’s hope it won’t be needed.”

“Did you notice that all the lambs and piglets and kids are females?” I asked.

“I had, but I’ve been too busy to think on it much. Do you think it signifies?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “Are the rocks hot yet? That poor dragon is shivering.”

“There’s a sequence of words uttered that I never thought in my born days to hear.”

I stripped off and joined the baby dragon—I supposed I should call it Eldingorm, since it had named itself—in the sauna, which probably wasn’t wise of me but a shirt and a pair of trousers were not much protection against claws and teeth. And anyway somebody had to ladle the water.

Once in the steam—it barely fit, taking up the entire floor—Eldingorm turned around three times like a cat, curled up small, and went to sleep with the immediacy of any overstimulated baby. Its shivering stopped, though the color stayed more blue than carnelian. Maybe it was supposed to do that?

I didn’t know anything about raising dragonlets. Were barrow-wights even a good source of nourishment for a dragon? If animated people jerky was adequate sustenance, we’d still have to move on once the undead ran out, for the sake of the local livestock and the villagers who depended on it.

I leaned my head back against the wall and let the sweat flood down my body. It felt like decades of bitterness were leaching from my pores, along with all the dirt and impurities.

Okay, maybe not all the impurities.

The heat made my head swim. I was about to lie down on the bench and regain my equilibrium when a thread of cooler air tickled my face. I opened my eyes; the door cracked wider and my brother slipped in.

So much for feeling at peace. “Hello,” I said, because I wasn’t quite rude enough to say nothing.

A bucket of soft-needled pine branches in rapidly melting snow sat beside the door. Arnulfr fetched a handful and gestured with them. “If you wanted.”

Groaning, I got to my feet and turned my back on him. Vigorously but not too hard, he switched my back, arms, and legs. The icy water stung my skin, and the sweet smell of resin filled the steamy room.

For a moment, I felt well-disposed to him. I took up my own fistful of branches and switched him in return, not even trying to make it sting. The dragon kept snoring, little bubbles of eitr popping on its nostrils. It was just as well Eldingorm hadn’t wakened; I wouldn’t want it to confusedly assume Arnulfr was attacking me.

Gingerly, we sat down on the hot boards, and Arnulfr ladled another dose of water over the stones. Gasping in the steam, we leaned back. The dragon rumbled and stretched out as far as it could in the small space, tail-tip flicking.

“Have you thought about going to look for your nieces?” he asked. Your nieces, of course, not my daughters. Again.

You’ve got another one on the way. You won’t miss them much, I almost said nastily, but swallowed the harsh words. Years ago, I would not have gotten in front of it in time, and in my current state of lassitude I could not be bothered to start a pointless fraternal argument because I felt slighted.

Anyway, if he’d really wanted to manipulate me, we both knew he would have sent Bryngertha to talk to me—though possibly not in the sauna. He deserved some credit for doing his own dirty work.

“When were you thinking?” I asked. I felt his surprise without looking over.

“No one would ask you to go before spring—”

“It would have to be sooner,” I interrupted. “I need to get out of here with this dragon.”

“You’d travel in winter?” He sounded honestly horrified.

“Beats being killed as a witch. And I’m afraid Eldingorm here would eat anybody who tried, and then we’d both be banned for manslaughter.”

He chuckled, but I could see the wheels turning. He nodded at the man-sized newborn sprawled at our feet, now gently snoring. “How will you keep it warm?”

“Ask Bryngertha to knit it a sweater.”

“Her,” the baby dragon said sleepily.

“Pardon me?” I asked it.

“I’m a her, Mama.” Eldingorm blinked those huge eyes, which seemed luminescent in the dim light of the sauna.

“Well, I’m a him,” I told her. “So I’ll call you her, and you don’t call me Mama?”

“Yes,” she said, settling her chin on her talons again. “What should I call you?”

Not Father, either, I thought. Somewhere out there was a dragon who already claimed that honor, and I knew nothing about dragon society or how they felt about parenthood. But I suspected I would not survive it if I made one feel that he needed to defend his place.

“Uncle,” I said, with a sigh. “Call me Uncle Hacksilver.”

Arnulfr elbowed me. “Another niece,” he said.

“I guess that will make four all together.”

“I was hoping for a son,” he admitted.

“You won’t get one,” I said, thinking of what Aerndis had mentioned.

His eyes as wide as the dragon’s, he stared at me. “How do you know that?”

I snapped my fingers. “Sorcery.”

I wasn’t too worried about the women or the remaining cattle. If nothing else, the births we’d seen so far had all been swift, easy, and uncomplicated. That didn’t stop me from weaving a few spells of luck and protection around them, as I had promised Aerndis. I borrowed Ranndis’s little tablet loom for the project. I sat beside the hearth with the dragon on my feet like a mastiff dog and tried not to feel Ranndis’s gaze as she observed from by the stewpot, judging me.

All three women were over there, like Norns in the firelight, alternating stirring with knitting and spinning and carding wool.

Well, I could weave, and card and spin and knit as well. Let Ranndis have her judgment. And Bryngertha and Aerndis as well, if they were also after judging me.

I wanted to make belts, but I knew there would be no time for that much work, so I made each of the women a woven wristband, with tassels to tie it on. I had barely finished the third one when I heard Ranndis gasp from beside the fire.

Bryngertha looked over to where I sat, and Arnulfr and the two Ragnars beyond me playing at dice and ignoring my womanish behavior. “You men, it’s time to leave.”

Without protest, the other three got up. I snipped my last bracelet free of the tablet and stood as well, accidentally waking the dragon.

“Uncle?”

“Shh,” I said. “We’re going to the barn in a minute.” How the horses and cattle would react to the dragon was another problem, but I couldn’t leave her here when there would soon be screaming, blood, and babies.

I hoped the horses and cows would hold off birthing until morning.

It was growing bitterly cold with sunset, and I feared how bad it would be—but the stable was sheltered half into the hill and the bodies of horses and cattle kept it chilly, but tolerable. I threw the bundle of furs and blankets I had brought with me into a stack of hay and tucked Eldingorm in with a caution to watch her claws, lie quietly so she did not scare the horses, and not drip eitr on anything flammable.

I was the calmest of the four of us. I was also the only one whose daughter, sister, mother, or wife was not bearing. And I had to believe in the worth of my own witchcraft to protect the women. No one can accomplish miracles without committing.

“It won’t be long,” I said, watching my brother pace back and forth while Old Ragnar picked his fingernails and fussed over the cattle and Young Ragnar threw a knife into a pillar over and over again. The sound of blade sinking into wood was starting to get to me.

“You can’t know that,” Young Ragnar said. He managed not to sound querulous, which I gave him credit for.

I picked the spindle out of my pocket and started spinning hay again. The farm was going to need fodder. Half-Hand laid his halved hand on the side of the chestnut mare and felt the ripples that shuddered through her with every kick and squirm of the foal within. It wouldn’t be long now for the horses and the cattle, either.

What a joke, I thought. Then shouting in the farmyard brought me to my feet. I shoved the spindle back into my coat. Old Ragnar grunted at me. I wanted to tell him I wasn’t ashamed, just cautious. And there were men outside with torches. I could see their watery outlines through the barn’s one window, glazed with the translucent membrane from a whale’s gut.

“What do they want?” Arnulfr asked quietly.

“Send out the damned witch!” one of them yelled.

“Do you think they heard you?” I quipped dryly. All our weapons were in the house except my axe and our daggers. Eldingorm rose, shedding bits of hay, and padded after me. I was surprised and pleased that both Ragnars and Arnulfr picked up pitchforks and rakes and flanked me out the door.

“You son of a bitch—” one began, then fell back a step, squeaking, when he noticed the dragonlet.

“What the hell is that?”

“A dragon, Einar,” Ragnar said. “Get of the big one that flew away. You know. The one that caused the eruption. The one my old shieldmate Auga here bargained away from us, which is the only reason you and yours might make it through the winter.”

The ringleader—Einar, I supposed—snorted in an unlovely fashion. He had an exquisitely punchable face, but I restrained myself with an effort. I’d hate to see Eldingorm get hurt trying to defend me.

I kept my hand on my axe, though.

“Right,” said Einar. “Bargained with a dragon.”

“There’s the proof,” said Ragnar. “And look, here’s my son and Arnulfr, returned to us from the grave by dragon’s magic.”

A scream from the house hit us all with the force of a big wave breaking. The five threatening villagers stepped back as if someone had shoved them. They scowled at one another, blinking in confusion.

Einar hefted his torch.

He had a sword in his other hand, I saw through the dancing shadows. I shifted my grip on the axe, though I really didn’t want to kill anyone tonight.

Eldingorm hissed, her neck elongating. I laid my free hand on her shoulder. Her hide was hot as sun-warmed metal.

“What,” said Half-Hand. “You thought we weren’t affected by the weirdness?” He waved behind him. “Every mare and cow in there looks like a bladder blown taut.”

“The dead walk, Ragnar,” Einar said.

Yes and here they are. But I had enough wit not to say it.

Another scream from the house, its sharpness deadened by turves and timbers. Einar jumped. To be fair, I think I jumped as well.

Eldingorm made a peculiar burbling noise. “Hungry.”

I looked at her, for the moment ignoring the sudden interest that the villagers’ spears and axes had taken in us. Her tongue flicked out like a snake’s, tasting the air, shimmering bright with eitr.

Out among the badlands, in the direction of the village, something howled, inhuman.

“Stay,” I told my brother and Ragnar and his son. “Guard your families and the farm.”

Arnulfr scowled at me. “What do you think you’re doing?”

“Eldingorm and I are going to fight the draugr, so they don’t overrun the town.”

“That little thing?” said one of Einar’s friends.