“One day, you kids will get out of here.”

These melancholy words made up a mantra that Mary Frances Barron would hear daily, spoken to her by her own mother. It was a warning, a prayer and a promise all wrapped up in one — the desperate hope that Barron and her sisters would make it out of their tiny Pennsylvania town that epitomized “one more rusting relic of Appalachian despair.”

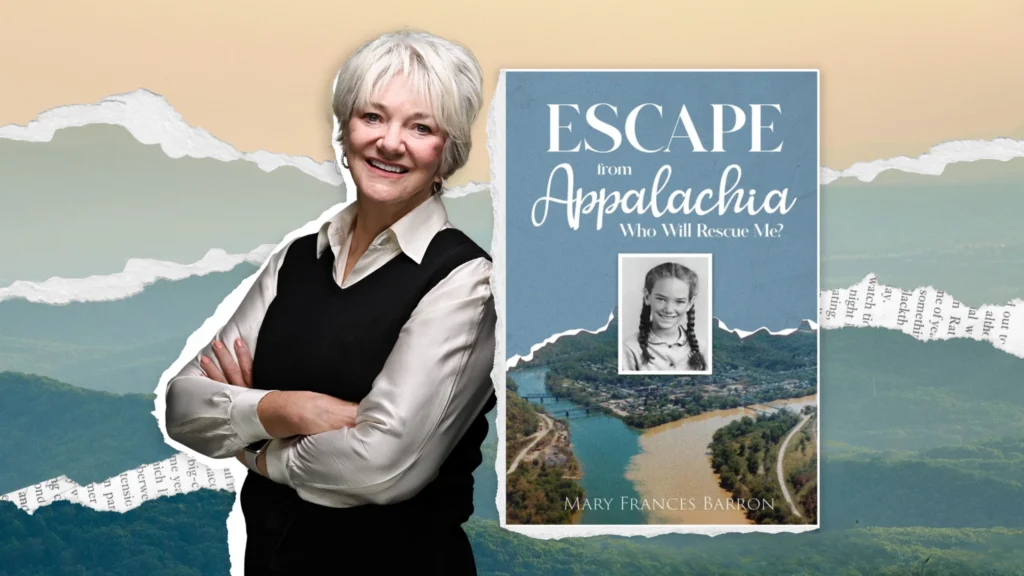

Her memoir, Escape from Appalachia: Who Will Rescue Me? balances that harrowing origin story with a deep sense of love and thankfulness for the people in who showed her it was possible for her to escape the clutches of poverty and hardship. After all, Barron was indeed able to get out of there. Now a successful businesswoman, she brings a fresh perspective to her tumultuous childhood and an awareness of the stark dichotomy between the poverty of the Rust Belt and the rest of the country.

Now, Barron speaks with us to go into her memoir in depth — the history of exploitation and industrialization that led to such economic despair, the catalyst that drove her to penning this story and the reason why her heart, after all these years, still calls Appalachia home.

Q: Your voice can be described as “witty and outgoing,” despite the hardships you faced. How did you strike a balance between humor and the gravity of the challenges portrayed in Appalachia?

A: The Appalachian culture is imbedded in storytelling. The low literacy rate of our culture underpins the rich tradition of oral narration; we pass down stories through generations, while books and libraries are not as valued. Even today, the school district serving my hometown and the other river towns in the district (Albert Gallatin School District), has recently closed all the elementary school and middle school libraries. The message is clear: even today, literacy and reading are not considered essential.

Rather than relying on the written word, with the lower literacy rate compared to the rest of the United States, the strong storytelling culture survives as a way to explain ourselves — to each other, our families and the outside world. Hardship and survival remain the standard of growing up in the Appalachians. Of course we try to find humor in the absurd.

Q: Appalachia’s story is deeply tied to coal mining and its aftermath. How did you approach weaving environmental devastation and its social repercussions into this personal narrative?

A: King Coal; the rape of the Appalachian environment continues. The effects of generations of exploitation, abuse and neglect are evident in the entire mountain corridor. A huge chunk of the once verdant American landscape is cratered and hidden behind the country roads and shuttering small towns. But people are numb to its effects. The threads of poverty, isolation, addiction, depression and violence are stitched into the very fabric of the people’s soul. People outside Appalachia cannot grasp the effects of living in an America with little hope and a total lack of understanding from their fellow Americans.

With bleak surroundings and dried up industry, the air and water were contaminated beyond imagination, and the people were dirt poor. Life in the entire Appalachian region was a day-to-day desperate getting by. To understand the complexity of my childhood, one needs to grasp the history of the area, the mindset and brokenness of the people, and the hopelessness that comes from living in poverty — that comes from just scraping by.

Q: The mantra, “One day, you kids will get out of here,” highlights both hope and despair. How does your journey reflect the tension between a desire for escape and the pull of home?

A: The children of Appalachia are sometimes victims of the magnetic attraction of the Appalachian valley for her native kin that is not unlike a seductive drug that calls their name. Every moment of every day, it latches on to the noise in the heads of her inborn sons and daughters and chants the repetitive song, “COME BACK TO ME.”

“Once that river valley latches on to you, you hain’t goin’ nowhere. Y’all will all wise be back. She is some mean Mother … Once the river valley starts flowing through your blood — you’ll never get out.”

People stay. They cannot get away. It’s a thread that seems to reach up from the earth’s core and connect people to the hills with a song of temptation like nowhere else. Caressing the soul while at the same time smothering ambition; numbing the people into complacency. The mother mountain gently wraps her arms around an inborn son or daughter’s body, dancing for a while, playing for a time, but finally squeezing much of the vitality of life from her children. It is a living, breathing organism, but broken, present, and calling us by name. Delicately, it calls its offspring…

Q: The book blends your own story with historical context. What was your process for integrating factual history with deeply personal storytelling?

A: The stories of Appalachia are ingrained into its native sons and daughters. We grow up hearing them over and over and the narrative becomes embedded into our very DNA. Surviving in the environment we learn first-hand from the card that has been delt to us. It does not change. Those of us who have made a very real attempt to understand the seduction of the mountains have had to search beyond the shadows of the woods and the mist of the river valleys and connect with a process of analyzing factual data. Hands on grit and resilience taught me to deploy whatever I could scrape together to uncover history’s lessons. A step toward understanding my true self.

Q: Appalachia is often stereotyped or misunderstood. What myths or misconceptions did you aim to challenge in writing this book, and how do you hope readers’ perceptions will shift?

A: I decided that I absolutely must write a book about growing up in a small town in the backwoods and life in Appalachia when I was getting an MBA in California. The program was for people who owned their own company or were vice presidents of publicly traded companies. We were from all over the West Coast — meeting monthly at each other’s rather swanky place of business with our professors. I was the only female in a group of 17 and all my cohorts could not understand and did not believe the dichotomy I kept telling them that exists in America. (They all grew up rich and endowed).

Somehow, I could not articulate what life is like along the rivers in the coalfields, the day-to-day struggle. I experienced an attitude that seems to permeate the culture of America, that people in the Rust Belt are conniving to exploit the government (and the pocketbooks of taxpayers) to get a free ride of benefits and services. That they want to be addicted and unemployed.

I didn’t start really working on the book until well after I had sold my last company and finished being on boards — maybe four years ago. I put it aside for a year at a time just because I thought that I was an imposter. I still battle with those thoughts. But I want people to read my book and walk with me through the underbrush and really see that real people are today living in this environment and trying to get by.

Q: The story touches on cycles of addiction, depression and poverty. What role does your relationship with your mother and community play in highlighting both the burdens and strengths passed down through generations?

A: With little opportunity for any kind of a livelihood, generations of people living in the Appalachians are in despair. Yet they stay. Communities of people are stashed together in areas that have little access to the outside world, apart from the school bus and the postman. Stratums of existence, layers of humanity all struggling to get by, to have day-to-day meaning, or live another day. Poverty is accepted. Many are addicted and depressed. Violence, for many, is a way of life.

There was a steady reminder from my mother to get out. On my path toward survival, and in looking back on the trajectory of my life, there was a discovery — a realization that somewhere there is a light that beams down on me. In spite of my stupid decisions and tripping over calloused predeterminations of what I could be, I found a star shining on me through the others who inspired me to first understand and then gently encourage me to reach out of my own cocoon of darkness. I began to understand that I have been sent true angels who touched me throughout my life and gently led me beyond the beaten path.

Q: The book promises a restoration of a resilient spirit. Can you share a moment in your journey where this resilience shines the brightest, and what message do you hope readers take away about overcoming adversity?

A: This book is a testament of how a resilient spirit amid abject adversity is sometimes showered with the quiet caring of the hidden angels surrounding us who light our path; the souls whose silent walk restored my heart, acting as beacons; quietly moving with me.

When asked to share a moment where this resilience shines the brightest….

My dog George was my constant companion, by my side with unconditional love. Yes, a dog.

Aunt Mae Mae inspired me by reading to me on her porch swing and teaching me Bible songs.

Miss Berg. She loved every one of her kindergarten students, wiping nose drippings and drool with her ironed handkerchief.

John Dick. Sitting with me after a long shift in the coal mines, taking time to explain love of family.

George Dearth. Hunting ruffed grouse with me with his bird dog BeBe. Quietly holding my hand.

Susie and her family. Teaching me generational kindness and tolerance.

So many others…

It is my hope that the reader will amble along the path with me, learn from my many mistakes and laugh with me at the absurd. Along the way, they may wonder at — and then understand — how one’s surroundings and inherited DNA, dismal as it may be, can be deployed, thanks to help from the everyday saints among us.

Escape from Appalachia: Who Will Rescue Me? is available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble and Bookshop.

RELATED POSTS:

Story of Resilience Recounts Escape from Poverty and Hardship in Appalachia